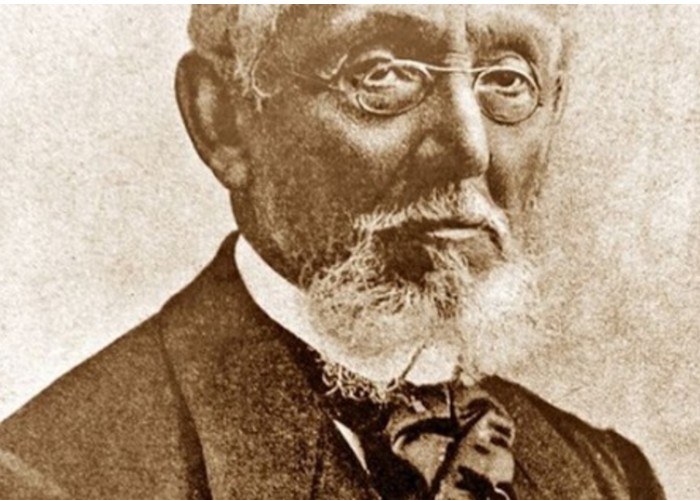

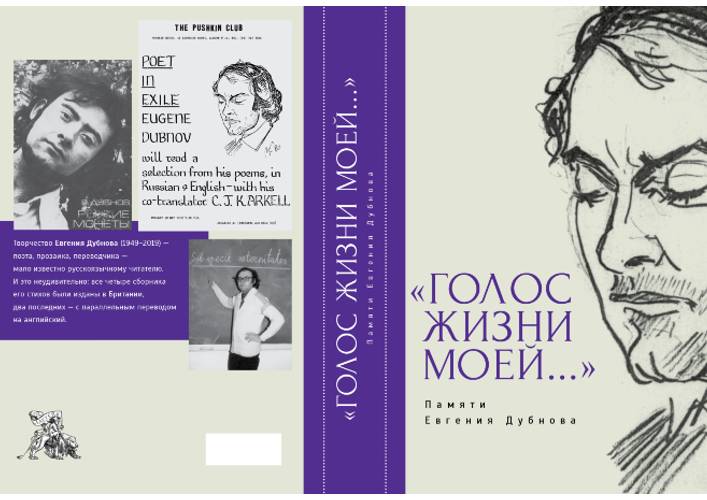

“The Voice of My Life…” In Мemory of Eugene Dubnov.

Articles about the Work of E. Dubnov. Memories of his Friends. Prose and Poetry.

Compiled by Leah Greenberg-Dubnova. St. Petersburg: Aletheia, 2021.

Eugene Dubnov, a bilingual poet, novelist, and translator, passed away in Jerusalem in the summer of 2019. Two years later, I am holding a book published in his memory: it contains articles about his work, memories of his friends, as well as his poems and prose. Flipping the pages, I feel as though I am at a literary soiree organized in memory of the poet. It begins with opening remarks by his sister, Leah Greenberg-Dubnova. Without her love for her brother, and her fidelity to the family memory, this book would not exist. As she constantly emphasizes, working on Eugene’s heritage was an opportunity for her to overcome the distance that circumstances often place between family members: At times, it seemed that I got closer to him just by looking through his archive, all those carefully preserved letters, poems <...> Everything that was so far from me in time, suddenly seemed to come closer….

Dubnov’s friends from Jerusalem, London, and Stuttgart share their memories of the poet; colleagues talk about working together on translations as well as on various publishing projects. These are followed by observations on the peculiarities of Dubnow’s poetics and his major themes and comments on particular books of his poetry. We hear Yevgeny Dubnov’s own voice in excerpts from his interviews over the years. I listen to all speeches with interest, and along with gratitude to all speakers, a desire gradually grows in me, a wish for the evening to be over, so I could go home with a book under my arm, settle with it in front of a floor lamp, be alone with the poems, so that the most important conversation would begin finally, the conversation for which the poet lives, or – as in this case – lived.

In the thematic grid of Dubnov’s poems, the motif of a route, and its railway version, stands out clearly, with keywords such as railway station, platform, conductor, semaphores. (Akhmatova spoke of the importance of repeating individual words as part of the poet’s perception of the world.) This motif is often associated with feelings of melancholy, loneliness, and something that has not yet been accomplished. Hence the carriage, not believing in the journey, the train station pain, the platform, smelled with longing, the frosty mantle of the station. But all this is only an illusion of movement. Dubnov’s lyrical hero is not going anywhere: he is always at home, inside himself. It is not for nothing that looking out of the window is so common in his poems: the window is one of the most important symbols in his poetry, so much so that one small lyrical cycle is titled At the windows:

And looking out the window at tea this March morning,

You feel yourself slowly marveling at life.

And so I once more face the windows,

Whimsically read by ice…

And then

You suddenly know

In the cities

The gait of May

And you’ll open

a window to let in the blue,

So that autumn

would open in the spring *

The presence of others in the lyrical space of the poem is also illusory. Sometimes this presence is simply hinted at with a light touch, as in this early poem from 1967:

At night, hands

rest anxiously and sensitively on my shoulders.

I stand for hours

pressing my face to the window… *

But the lyrical you in most poems is most often a reference to oneself, a conversation with oneself (Look, how the candle is blown away, To see off the ships you have come to no one knows where). The ability to be alone with oneself is the sign of a great mature poet. And nowhere is this ability more evident than in poems whose very subject matter suggests a leap into other geographical spaces. Dubnov’s geography can be traced by listing his poem titles: Near Thames, Scotland, 1976, Ireland, Canadian Lines, Paris Guide, Edinburgh, Journey to Jerusalem, Jerusalem Lines. Yet in these poems, Dubnov is not a place-writer (his ironic word for it). Although numerous details testify to his amazing power of observation and the ability to convey a landscape with a few words, the important thing here is the poet’s own excitement, his tears, and fears, doubts and hopes. Dubnov’s life was such that his most dear and favorite places were both in the south (Jerusalem) and the north (London, Riga, Tallinn). To me, a reader from the north, his “English” poems seem closer, especially the ones about London, the Thames, and Ireland. The traditional fog and rain are not mentioned very often in them. Dubnov has a gift for creating a landscape using words and phrases seemingly neutral about a particular corner of the earth. Here are examples from his Scottish pictures: misearbly idle land*, light flute, the grass rustles, the water sparkles…

Often, though, different countries and cities merge in the same poem:

The blue air of Riga

Over the Paris river. *

Or from another poem:

The hour when a swallow flew over the Thames

Through the blue dawn,

A blizzard touched the heated forehead

On a Moscow square. *

In the poem Scotland, 1976, a large shadow falls on the sky like a boot. It is a man walking, all stained red*. These are Macbeth’s footsteps. The first line is a quote from Shakespeare, in the original. There are many epigraphs in foreign languages, literary allusions, and interjections in this book. But the author’s erudition does not demean the reader, as is often the case in modern “intellectual” poetry. The poet supplies translations of all quotations, in addition to detailed historical and literary explanations. At the same time, Dubnov’s reader experiences not the humiliation of ignorance, but the joy of knowledge, the joy of discovery, and new turns of thought.

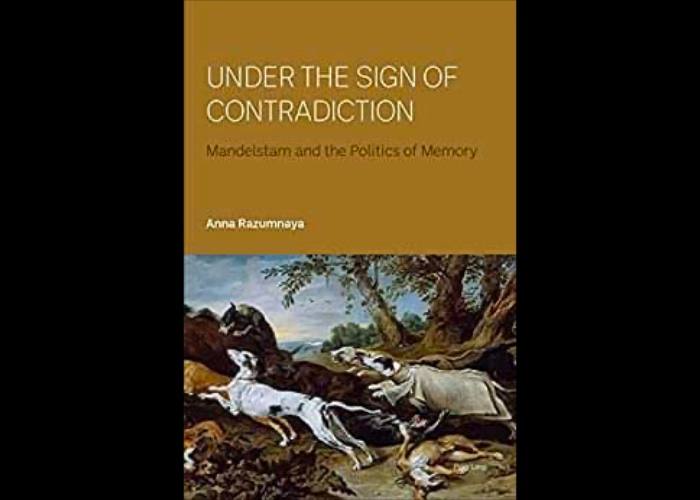

According to the recollections of people who knew Yevgeny Dubnov well, he had a great sense of humor and could fool around and laugh until he dropped. In the book, the reader will indeed find many lines written with Mandelshtam’s mischief:

Smiling, stop by

Shaking off the rain,

untie your thin scarf

And tell me about your dress

The one you bought yesterday

To wear to parties,

This dress, just like in the movies

and it ain’t cheap

And for the price,

A fashionable cut on the back… *

But no matter what the poet writes about, his main theme in almost every poem is the poetic word itself, its mystery and its life, its power, and the poet’s painful journey from silence to sound. That is why the presence of words such as rhyme, a metrical foot, names of metrical feet (all my pardons, all my anapests, all my promises…) is so organic. The fusion of poetry and life creates an expressive ambiguity: What eternal reason/Troubles the branch and torments the leaf (лист)? What are we talking about here, a tree leaf or the blank white sheet of paper before the verse is born?

One of Dubnov’s friends recalls his words about metaphor as the basis of the poetic image. In the fabric of his poems, metaphors are not crowded together, yet they combine a logical structure with novelty and surprise:

Burying the crests of the shore, all in tears,

The shroud of foam is decaying before my eyes… *

A list of successful epithets, neologisms, and comparisons in Dubnov’s poems would be quite long. The leaves of the past fall, the heavy cry…crunched in the webs, the guttural speech of the squares, the bony uneven hands, the leafy chill, the grass is robust like a passage from the larynx…*

Dubnov’s poetic grammar is also quite interesting. For example, the poem Standing on the bridge on an unsmiling morning… has five stanzas, each of which works as an extended participle phrase and begins with a gerund, in which the verb is absent. Another example is the subordinate clauses with an absent main clause. Of course, Dubnov was not a pioneer in this. The grammatical interdependence of words is often absent in poetic language, and traditionally dependent elements are transformed into independent ones.

It is also worth noting some metrical and strophic features of Dubnov’s poems. For example, when a combination of short and long measures is used in the same stanza, the short odd lines often contrast sharply in their size with even ones (not vice versa, which is more typical). These are combinations of one-foot chorus and five-foot amphibrachs, one-foot and three-foot anapests, or two-foot and four-foot iambs.

Yevgeny Dubnov’s life, alas, has come to an end. The man’s passing is irreplaceable for his relatives, friends, and interlocutors. But there is also a certain light-filled comfort in the passing of the poet:

No youth and no shelter, the years

Are gone – nothing but a word and a footstep.*

…What is left for us, in the end, is a joy we experience retracing the poet’s footsteps.

* Lines from Dubnov’s poems are rough translations from Russian.