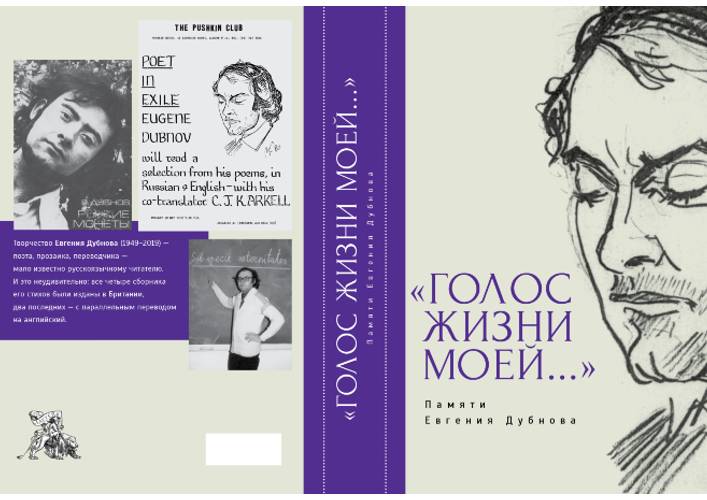

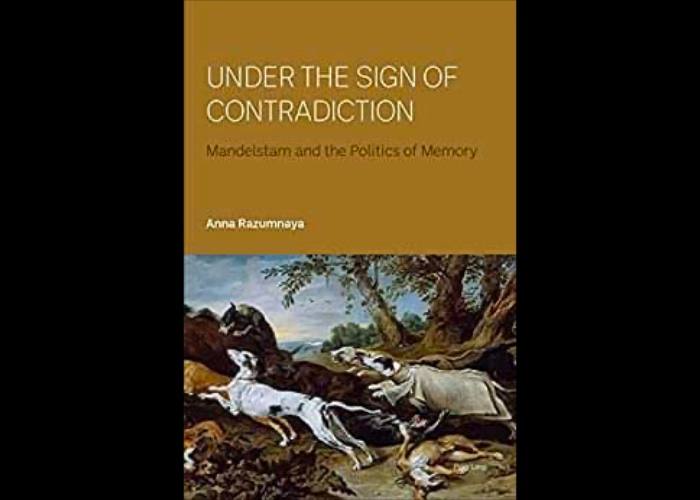

Anna Razumnaya, Under the Sign of Contradiction (Peter Lang, 2021)

The Foreign Agent https://foreignagent.substack.com/about

Feeling around for Something Human (a recent survey of Russian public opinion by Shura Burtin) https://tinyurl.com/2p8kyzbt

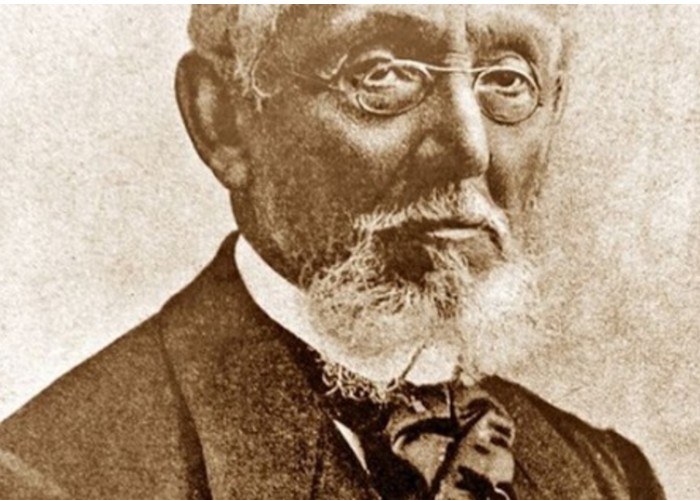

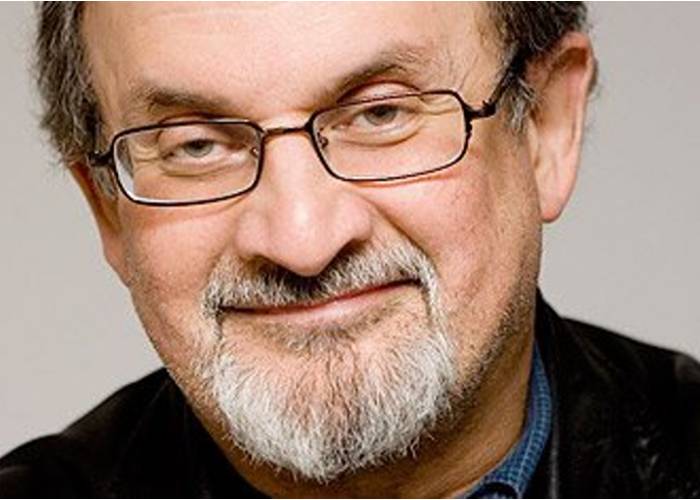

Anna Razumnaya’s account of Osip Mandelstam’s last decade and his inner dialogue with Stalinism has received no reviews whatsoever, either in academic journals or in more popular publications. I was astonished to learn this, since I take Mandelstam’s importance for granted and I know of no other work like Razumnaya’s. Fifty years ago, when I was first studying Russian at university, Clarence Brown’s ground-breaking study of Mandelstam’s poetry and Nadezhda Mandelstam’s memoir of her husband’s life were widely read. Their joint picture of Osip Mandelstam as a heroic, almost saintly genius was part of the intellectual currency of those Cold War years.

What makes the lack of interest in Razumnaya’s work still more dismaying is that her subtle, balanced account of Mandelstams’s last decade and his imaginative engagement with Stalinism is as relevant to our own times as the earlier heroic myth was relevant to the intellectual concerns of the Cold War years. Her choice of title – Under the Sign of Contradiction – is apt. The Mandelstam she portrays was indeed a heroic genius, and a great poet, but he was also a man who betrayed his closest friends and spent much of his last years searching for ways to reconcile himself to Stalinism. Razumnaya’s work can help us in the difficult task of understanding how it is that even intelligent and educated Russians can support Putin and his war.

Razumnaya’s impressive grasp of a variety of disciplines – architecture, European literary history, psychoanalysis, and philosophy amongst them – allows her to view Mandelstam through several different lenses. Among her book’s guiding presences are Dante – to whom Mandelstam himself returns many times in both his prose and his poetry; William Empson – for his understanding of paradox and ambiguity; Andrew Marvell – for the deftness with which he negotiated political divides, contriving both to defer to Oliver Cromwell and to express sympathy for the executed Charles I; and the psychoanalyst Ronald Fairbairn. The following passage of Fairbairn, quoted four times in the book, is a key to her understanding of Mandelstam’s contradictions: “It is better to be a sinner in a world ruled by God than to live in a world ruled by the Devil. A sinner in a world ruled by God may be bad; but there is always a certain sense of security to be derived from the fact that the world around is good […] and in any case there is always a hope of redemption.” Both Razumnaya and Fairbairn emphasize the psychic danger of believing that one is the only sane person in a mad world. It is hard to hold to such a belief without slipping into an arrogance that is merely a different form of madness. It is understandable, therefore, that Mandelstam should have struggled to convince himself that Stalin’s Soviet Union was a good and rational world, not a world ruled by Evil.

The core of Razumnaya’s work is her discussion of the “Stalin Ode,” the complex 96-line poem Mandelstam labored over for three months during the last year of his life. Her most important point is that – contrary to the protestations of his widow and many of his admirers – Mandelstam was sincerely engaged with this ode at the deepest imaginative level. Through both sound play and imagery, the ode is intimately related to most of the other poems he wrote during his last years, and it cannot be dismissed as a belated, cynical but sensible, attempt on Mandelstam’s part to ingratiate himself with the authorities. Many of Mandelstam’s admirers still find this view of the ode shocking. This is understandable – it can be hard to let go of a beautiful and consoling myth.

The difficulty of escaping from group pressures and standing apart from the world around one cannot be overestimated. I was moved by the straightforward honesty with which, six or seven years ago, a young Finnish student told me of an unsettling experience of her own. She had been studying for a joint degree in Russian and Social Studies and her final year dissertation was about Russian nationalist youth organizations. In the name of research, she managed to enroll in a Putinite summer youth camp. She was sociable, charming, and a good singer and violinist. Her Russian peers immediately took to her and, to her surprise, she felt entirely at home in the camp. And then, after a week, suddenly realizing that she had already begun to absorb the nationalist and bellicose views of everyone around her, she experienced something close to an emotional breakdown.

Razumnaya currently writes a weekly blog about Russia and Ukraine, titled “The Foreign Agent.” In a recent blog, she referred to the philosopher Mikhail Epstein’s coinage of the word “schizofascism,” denoting a brand of fascism that passes itself off as a struggle against fascism. She went on to summarize a recent brilliant survey of Russian public opinion by the journalist Shura Burtin, emphasizing the prevalence of this and other kinds of split thinking. A particularly glaring example is the following exchange: “Did Russia attack Ukraine?” “No. That is, yes, but we were not the first.” Other examples of what is perhaps best described as “knowing and not knowing” (a phrase used by the psychoanalyst John Steiner) are still more baffling: “I changed currency today, bought some dollars. It’s alright, everything will be fine, soon we’ll disconnect from the dollar system.”

Razumnaya is not the first scholar to question the idealization of such figures as Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova. What is unique about her “deconstruction” – if that is the word – is its tact and sensitivity; she treats not only Mandelstam himself but also all her often mutually hostile witnesses with consistent respect. And the depth of thought with which she has examined Mandelstam’s inner contradictions allows her to write about contemporary Russia with unusual perceptiveness. I cannot recommend her blogs too highly.

June 2022