In his weekly column on RFI, philologist Gasan Guseinov reflects on revenge as a sad but effective tool for restoring world harmony. This is what Ken McMullen’s film «Hamlet Within» is all about.

*

Ken McMullen made the film «Hamlet Within» shortly after the beginning of the bloody Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022 without any connection to this war. But, as sometimes happens with a work of art, the metaphysical intent of a remarkable picture from the most unexpected angle can help one understand what is happening. Now that a year has passed since the film’s world premiere, this extremely rational and psychedelic film is becoming a linguistic document of our time.

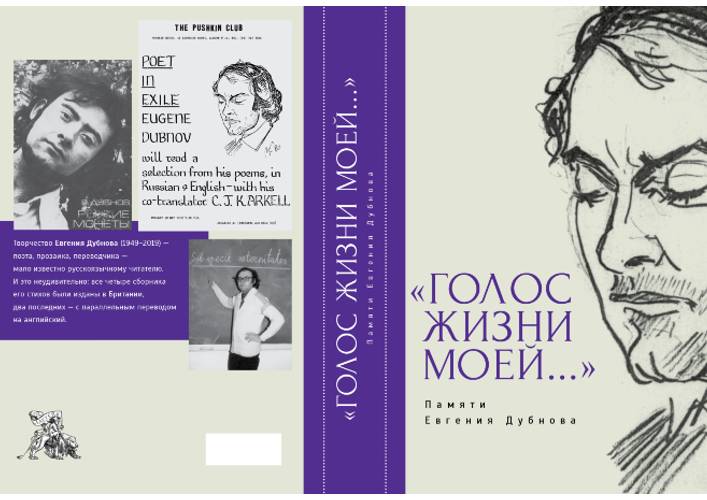

The hint that the director himself gave me in a conversation on September 7, 2024 was therapeutic for me. A few days ago, an old friend from the 1990s, Radio Liberty host Vladimir Toltz, died. In recent years, because of his illness, we had little contact, mostly by phone, but in every conversation one or other of the things Tolz had once said on the radio in his ironically smiling voice, a voice without anger, came to mind. I didn’t have enough stuff for an obituary, because where is it now, that radio voice? What will my memories of him mean to other people? Maybe talking about McMullen’s film is the right frame for such an obituary?

Ken McMullen begins with the voice. He asks where did the 900 famous actors of bygone eras who played Hamlet go; where did the medieval castles go, those witnesses to events both imagined and authentic? Who can explain exactly how this ghost managed to unfold a real bloody drama, the tragedy of war? Can something be born out of this ridiculous, comical stupidity that has kept people going for half a millennium?

McMullen is a master of incorporating a detailed analysis into an artistic statement. In two of his films, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida is a protagonist, playing himself. McMullen recorded an interview with the philosopher while Derrida was still alive. Don’t rush to accuse me of idiocy for this formulation. Both conversations concerned plagiarism and ghosts.

In “Hamlet Within” Derrida discusses plagiarism, or the illegal seizure of another person’s property, especially intellectual property. In another, earlier film, Derrida answers a reporter’s question about whether he believes in ghosts. Derrida answers in the affirmative: “And won’t I myself, who speak about myself today in your film, become a ghost after a while?”.

After the philosopher’s death, the remaining records, and especially the interviews conducted by McMullen, confirm this affirmative answer as convincingly as possible. Who is the man answering the questions? Where is he? We repeat again the question asked at the very beginning of the film “Hamlet Within.”

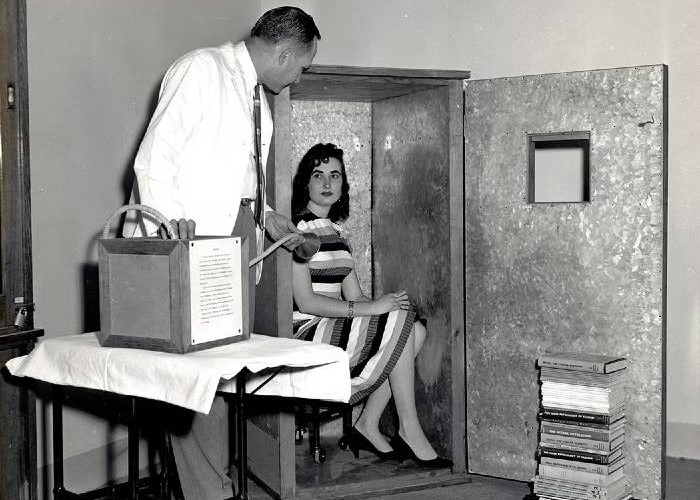

It turns out that there remains a voice. In the 2023 film, the voice is given to a ghost, the so-called shadow of Hamlet’s father, who gives a radio interview to his son, Hamlet Jr. McMullen explains the case as follows: this text, created to encourage the orphaned young man to act, is, in fact, only a voice, yet this voice comes not from the hero’s subconscious but from the radio. This voice belongs to the brilliant actor Ian McKellen. In McMullen’s film, he seems to be responding to Horatio’s call from the play:

Stop, obsession! And if you

are able to speak, then speak!

Tell me,

Is there anything in the world,

That can ease thy plight,

And show me the fountain of grace?

Reveal it to me,

Thy appearance

Does not thy appearance portend calamities to come?

And can my sight

Prevent what is to come?

It was the ghost’s ability to speak that McMullen seized upon. The latest and best Russian translation for our generation could be put into the mouth of a radio announcer.

HAMLET

What are you talking about, I don’t understand…

GHOST

I

Your father’s spirit, condemned

To wander the earth in the cold night,

and fast by day in a fiery dungeon,

Until my transgressions

that my sins, burning, shall not make the smoke lighter.

If I could break the spell,

I would turn over with the lightest of words

Your aching soul and tempered

Your fervour, and illuminate your eyes

With the glow of eternity, comparable only

To the glow of a star gone out of the sky.

One word,

And your hair will stand on end, as if

Thou on thy shoulders, my sweet Hamlet, carry’st

Not thy head, but a porcupine’s,

covered with armour of the strongest needles.

But this is a secret not to be divulged

to one who is of mortal flesh.

So listen to the other one… Listen hard,

When you really loved me.

HAMLET

Oh, my God.

Ghost

You must avenge

For the foul and vile murder.

HAMLET

Murder?

GHOST

Yes, the likes of which there is no such thing.

HAMLET

Then spill it, and quickly,

And I’ll soar on wings of vengeance

and I’ll reach my desired goal

Faster than a lover…

GHOST

Yes, I can see that,

You weren’t born to be a weed,

trampled down on the wharf of summer.

But listen. It was said of me,

That at the hour when I slept in my garden,

I was stung by a snake. Alas,

It was so, if I only knew

That that snake walks in my crown.

HAMLET

Aha, soul, so that’s what you were whispering…

My uncle…

GHOST

Yes, a vile incestuous man,

A monster, a scoundrel, a sorcerer.

His vicious mind, his shamelessness

Unreliable – have power,

Capable of tempting virtue too.

And the queen bowed before him.

O Hamlet, Hamlet, how could she

I, with my noble love

be replaced by a wretch whose talents

are but a prolonged nothingness and nothing but?

And can virtue be seduced?…

Though lechery be careful that the form

may not be at variance with the heavenly substance,

The divine vial is so fragile,

that the progenitor of lust, and that one,

Though he be of angelic rank,

will be satiated with what is permitted and become

A hunter of stinking offal.

But it’s late. It smells like morning dawn…

So, while I was sleeping in my garden,

Your uncle crept up on me and spilled a potion

Poured it into the portals of my ear

And thereby relieved me of my burden…

Yes, that concoction of herbal juice

has long been at odds with human blood,

And once inside, faster than mercury

It fills the exits and entrances

The natural corridors of the body,

And all its closets… Acid

That’s how milk curdles.

And so it was with me: a single drop,

And in a brief moment, a heavy crust

covered my body. Like this,

Soothed in a moment by my brother’s hand,

I was torn from my wife and crown,

I am unclean, unconfessed,

In all the bloom of my sins

I was cut off. And all my imperfections

In life, all my debts,

and all my other things – oh, horror, Hamlet, horror! –

I have them with me, and if thy blood

be not fish’s, thou canst not bear it,

How impossible it is, Hamlet, that the bed

of the monarchs of Denmark be made a bedstead

for adultery. Avenge yourself

As fast as you can. But remember:

Thou shalt not, my son, even in the darkest thoughts

Thou shalt not plot against thy mother.

Leave her to the Almighty. Leave her

To the thorns in this weak heart,

to prick it and sting it… So… Farewell…

Already the swamp firefly on the rotting bog

Blinks to me that morning is coming,

And its cold fire grows more and more pale…

Farewell. Farewell, but remember me.

(The ghost disappears into the ground, Hamlet falls to his knees.)

HAMLET

Well, what else, Lord of mercy?

Is it possible to bear this too?

What a devil!… Poor heart, hold fast.

Hold fast, thou weakening body.

(rising from his knees)

Hey, ghost, if you are able to hear

In the belly of the maddened globe,

Remember what I tell you:

Henceforth I will unhesitatingly sweep away

From the filing cabinet of my memory

All knowledge, all the book dust,

The archival junk accumulated over the years

of my inquisitive youth, all of the experience

of mistakes and unjust observations.

And all the forsaken commandments, but

one, yours. As long as my brain

Soiled with worldly things, I’m powerless,

And not even Heaven can help me. God,

O Heaven, O earth, what filth!

And that woman and that scoundrel

With a smile full of teeth,

Have ruined my former plans.

In Ken McMullen’s interpretation, what the Ghost says is not just the guilty subconscious of Hamlet’s son: without the Ghost, he knows who really killed his father and banishes from himself the very thought of revenge. In the film, the words of vengeance are spoken over the radio by the voice of the world order itself, which will be destroyed if everything is left as it is.

That’s why Ian McKellen speaks these words without affectation, even detachedly. And Hamlet Jr., listening to this speech through headphones in the recording studio, needs no excuse to start acting and speaking like a madman.

Because revenge is easy to imagine as irrational madness: it will not bring back the murdered, but it will also make the victim a murderer.

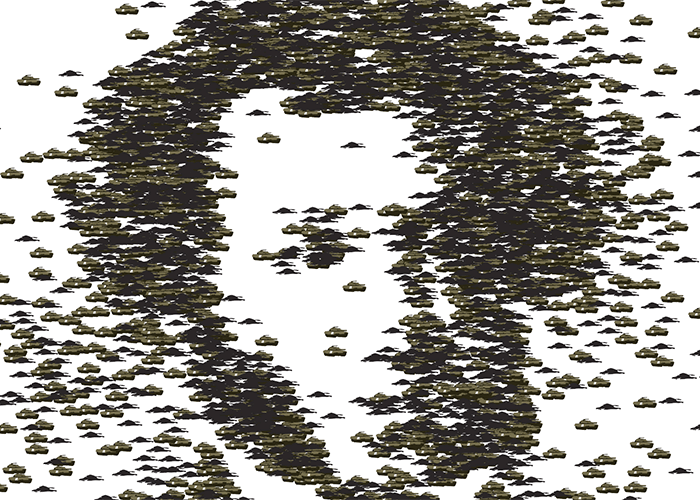

Decades ago, in Yuri Lyubimov’s Hamlet at Moscow’s Taganka Theatre, the main character in the play was a brown, tongue-less, menacing curtain. In McMullen’s film, the main protagonist is the North Sea, as if endowed with its own consciousness. And this consciousness is offended by the fact that no penalty is charged for the atrocity. From the villain.

In McMullen’s film, it’s not just the Ghost of Hamlet Sr. who has a voice. Philosophers, researchers of medieval chronicles, theatre scholars and actors speak as well. They read in Japanese and Russian, German and Spanish, and talk about their understanding of Hamlet, the action of which is supposed to be unfolding in London’s Globe Theater, which actually lives under the skull of each of us.

Is it arrogance bordering on insanity to think that a man avenging his father’s murderer is restoring global order? Many people think it is, and yes, it is presumptuous. McMullen films and records the voice of Shakespearean scholar Richard Wilson. “After 9/11,” says Professor Wilson, “we can’t still love Hamlet.” Wilson sees Hamlet as a “fanatic” and a “suicide bomber.”

In the preface to his translation of Hamlet, Andrei Chernov quotes Hamlet’s speech in a prose translation by M. M. Morozov. McMullen does the same in this film, only his character says it in the language of the original:

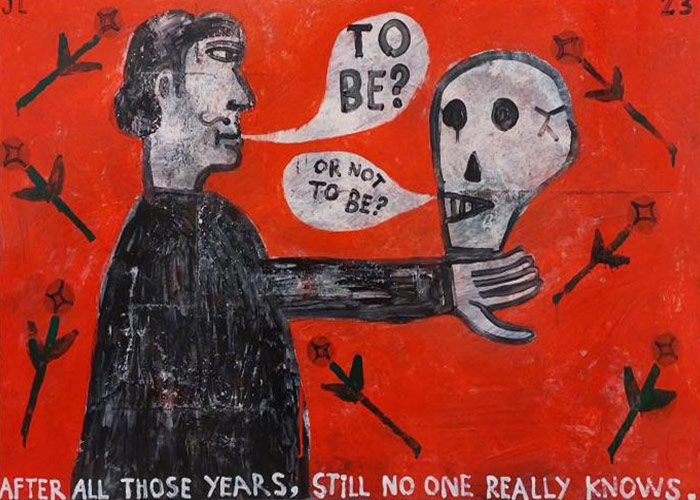

“To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep

No more; and by a sleep, to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That Flesh is heir to? ‘Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep,

To sleep, perchance to Dream; aye, there’s the rub,”

The refrain of the film is “to die, to sleep,” the words read by the narrator in German. This is the voice explaining why Hamlet has failed to turn away from revenge, to escape vengeance.

People who have fled from their subconscious to internal exile or to other countries look with anxiety and fear into the faces of others— those who are ready to take revenge—for February 24, 2022, for October 7, 2023, for the poison poured into the ear of the old king of Denmark.

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, everyone, or almost everyone, perishes. But the truth is restored, even if it seems ghostly or trivial.

_________________

Translated from Russian by Suzy Foster