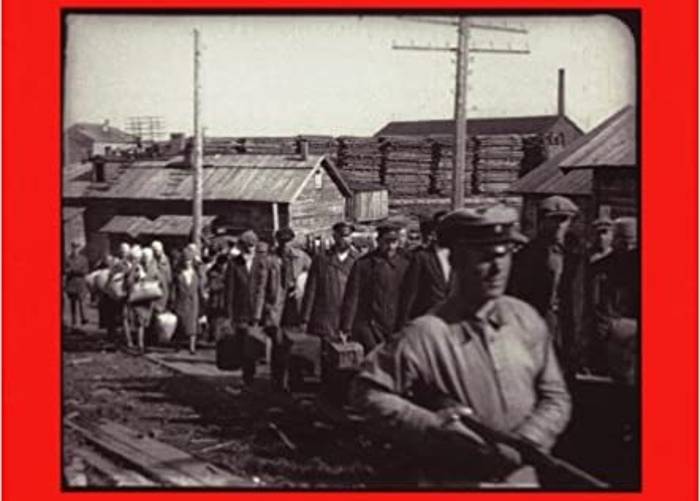

It is 1994. A recently arrived political refugee from a former communist country, I am a student in the MA in French program at a Southern University, where my best friend, B, introduces me to many things Americana. B is not your typical American—or so I, who have only been exposed to American values specific to the South—thought at the time. He is an intellectually curious young man who reads French literature, composes music and also happens to be some kind of computer genius. He is also extremely sensitive, concerned about the environment, and never watches TV. Now, although at the time he didn’t seem at all like your average American, for anyone reading this in 2021, it is clear that he was, in many ways, a typical American student.

Once, B tried to convince me that anyone can be anything they identify with, so long as this is their desire. For instance, he, an American, can be Australian, if he desires to identify as an Australian. Has he ever been to Australia? No. Is there anything specific in his biography that gives him a special connection to Australia? An ancestor? No. Or, maybe he has studied Australian culture and now he feels very close to it? No, nothing. He just feels like identifying as an Australian, and who am I to say no?

It was, of course, infuriating to witness this caricature of tolerance, because this is what this was: it was a part of a conversation about “tolerance,” which was expressed as a performance of identity: I can be whatever I want to be. The question that B never seemed to ask himself was: what is being?

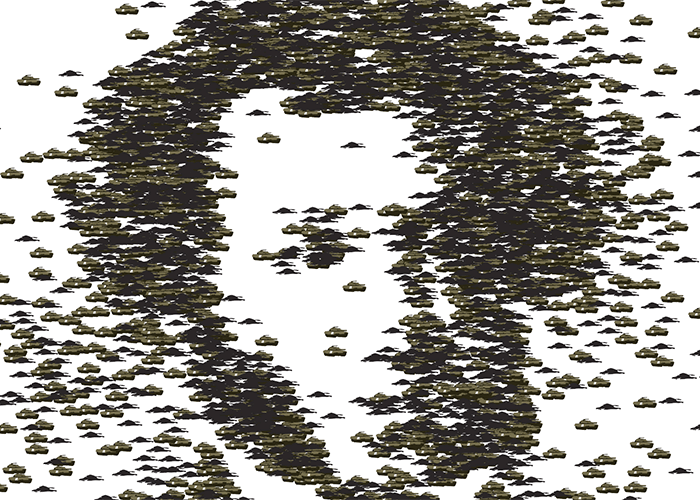

At some point in their history—and I am not sure when this happened, but it certainly preceded my arrival to this country—Americans stopped simply being, and they replaced it with identifying as. When one no longer is, one can be whatever and whoever one wants, because one can pick and choose anything in the Identity Store (with thanks to Lionel Shriver for this expression) like a piece of candy. The irony is that B shared exactly the same worldview as some of the Americana he most despised: in this case, Las Vegas and Disney World. For, what are all those copies of countries one sees in these Americana on steroids if not being-as-identity? Copies of being from other places that any American with an adequate wallet can buy for himself and identify with? I identify as because I am incapable of being anything. I identify as because I have no roots and I can copy your being and reproduce it until your being is no more than an empty Campbell can of soup to display in a museum. For which I will get a million dollars.

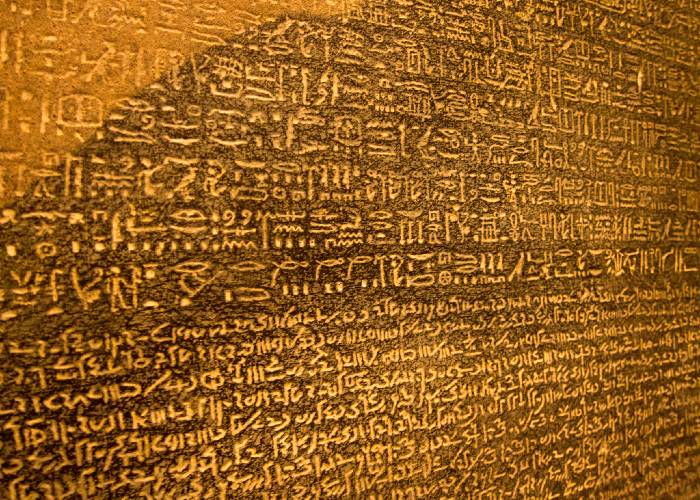

If you are skeptical that “I identify as” is an American ideology, try to translate these words in another language and you will see how unnatural they sound. Translation is always the best test to see where a concept originates from, and if a concept is English at origin and it was created in the past hundred years, you can be sure that it started in America.

Forward to more recent times: since desire is mimetic (and don’t take my word for it—read Denis de Rougemont and René Girard), we now live in a world in which “identity” has replaced being, a world of Americans-who-identify-as-Australians, and whose presence is so vocal and overwhelming that the Australians are starting to express concern. How come, they say, these fake Australians are getting so much more attention from the media and their demands are receiving more consideration than those of real Australians? At this, the Americans-who-identify-as-Australians reply that their feelings are hurt, that the Australians are a bunch of hateful and bigoted people, and, in fact, they are not even real Australians, the real Australians are them, the Americans, and they can prove it, because they now have passports that say “Australian” on them. This is insane, the Australians answer, we are the real Australians, and their insistence on their “identity” is proof, as far as the Americans-who-identify-as-Australians are concerned, that the Australians are a hateful and bigoted people. And so, the Americans are starting to prosecute the Australians for a hate crime, which they have labeled “Americano-as-Australo-phobia.” This is how the Australians have turned, eventually, into Nazis and the Americans into Australians, under whose flag they are now competing at the Olympics.

OK, some of you will say, this is a funny metaphor, or whatever it is, now we get it, you are just using poor B to hide your “Americano-as-Australo-phobia.”

First of all, B is a real person and the story about the Australians is real. What I am saying is that any ideology has behind it another ideology that you may not be able to see because you are already within it, and you assume that it’s a universal way of being in the world. But your assumption is simply based on an American premise. It is because you see the world within the American lens of identity that you believe in the first place that X can become Y. If one were to do a world survey, I guarantee that one would discover that the people who reject this ideology most viscerally are peasants, specifically, peasants from non-western cultures. This is because peasants have a worldview grounded in being. A worldview grounded in the earth, with which they are in touch every day. The real and not the copy. People who believe in the copy as the “real thing” (another American concept that can only appear in a culture where the “real thing” no longer exists, and so it becomes an Ideal) are all from an urban culture, a culture of mechanical reproduction (see Walter Benjamin). To believe in “I identify as” means to believe that a copy is more real than the real insofar as what you identify with is a copy of something that precedes it. The consequences of this ideology are that when being becomes “identity as,” we are one step removed from identity as commodity, and pretty soon your “identity” is being sold on the “marketplace of ideas” (another interesting American expression, which assumes that ideas are just like any other good that can be bought and sold) to the highest bidder. Your very being is turned into an empty can of soup that a Disneyfied American plays with while he lectures you on the evils of capitalism. Because, above all else, this American-who-identifies-as-an-Australian is an activist who fights capitalism.

Now, for some people—and I confess I am one of them—capitalism is a system that originated in 17th century Florence with the modern banking system, a system that exists outside of my being and which allows this being to function in the modern world. It is a necessary system, but it doesn’t touch my core, which is outside of it. Not so for the American-who-identifies-as-an-Australian. For this type of human, “capitalism” is synonymous with anything that he happens to dislike. The paradox—the enormous paradox—is that this type of human has a core that has been entirely infected by the very logic of capitalism insofar as he cannot see anything in itself (Adorno says somewhere that when capitalism touches everything—and it was his opinion that in America it touched everything—people can no longer see the “in-itself” of a thing). When everything is simply a copy of a thing that doesn’t exist because nothing is real, existence itself becomes a commodity that can be copied, multiplied and reproduced in the Identity Candy Store. The American-who-identifies-as-an-Australian treats his own being and that of others as commodities, not because he is evil—in fact, he is a very nice person—but because he is incapable of being. He is incapable of being, and so everything is for him an “identity,” that is, an impersonation of being. He can no longer say “I am” because he can only understand “I have.” “I identify as”: a mockery of being. Being as caricature. Identity as the absolute commodification of being. To believe in the ideology of “I-identify-as” is to believe that the copy is more real than the real. (Don’t take my word for it, read the works of almost all the French philosophers of the past hundred years, and more than anyone else, Baudrillard—A Perfect Crime. Ironically, some of these philosophers are being accused of having created this ideology, an accusation based on one of the biggest cultural misappropriations in history, which is that of French thought by American academics).

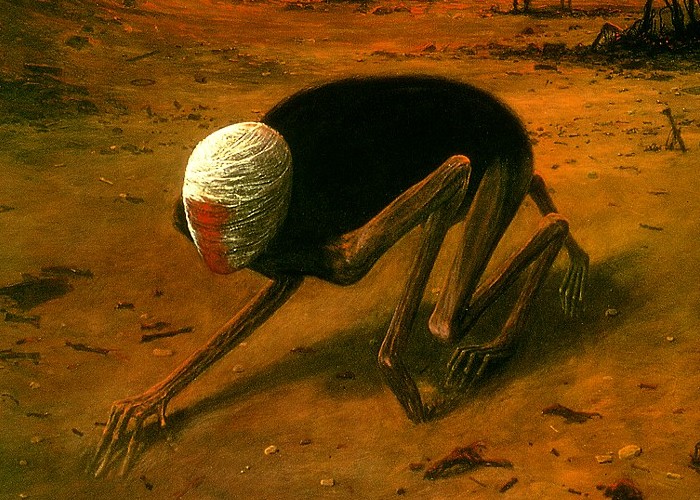

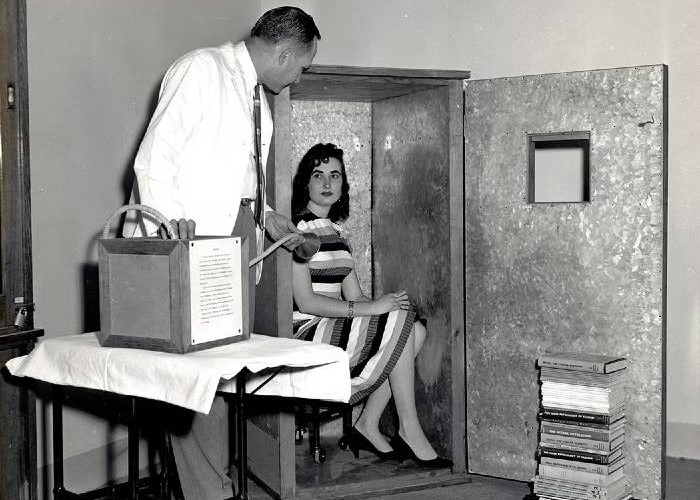

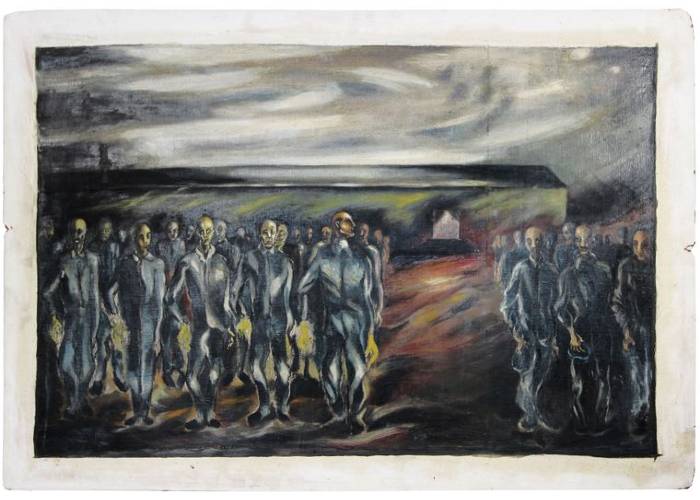

This American ideology presents itself as an ideology born of a desire for tolerance and inclusion, but, in reality, it ends up harming the very people it claims to help. Example: I recently applied for a job, and I had to answer a series of questions for Human Resources, among which “Do you identify as disabled?” I answered “yes” only because, of the three options presented to me, that was the only one I could choose, but the fact is that I do not “identify” as disabled; I am disabled. The phrasing of my prospective employer, which gives the appearance of concern for my disability, is, in fact, insulting, because it implies that disability isn’t a reality, but some kind of spectacle or performance. Anyone can claim that they “identify” as disabled, and insofar as identity is, in the new ideology of our times, a feeling, there is no objective way of rejecting any “identity.” If anyone can appropriate disability simply by making a statement, the logical consequence is that my disability becomes meaningless. In fact, the framing of disability as identity is a direct invitation to fraud because it invites all potential opportunists to appropriate something that isn’t theirs in order to score some points. These opportunists don’t need to live the daily experience of my physical disability, which involves huge expenses for caregiving, constant fights with the healthcare system, and extensive planning for things that most people take for granted, like getting from point A to point B; and yet, they can get the status of disabled simply through a performative act, which is, clearly, the only thing my prospective employer is interested in. The apparent concern for my disability is, in fact, a mockery because it completely invalidates its very reality. But then, why should this surprise us? After all, “identity” is, by definition, a fiction. Identity is something we construct in our heads, it doesn’t exist in the palpable reality outside of them, and so, a world that has replaced reality with identity is doomed to be a world of ghosts and mirrors that we all throw at each other and through which we grasp like madmen. Do you know what a world of infinite mirroring resembles most? Luna Park. A lunatic asylum. You know, the place where you can find all those people who “identify as” Jesus Christ.

I need to repeat what I have already said about my friend B because it is very relevant to our discussion: B is a real person. He is also one of the nicest, most sensitive and well-intentioned Americans I have ever met. The ideology of the Americans-who-identify-as-Australians is the ideology of some very nice people. I know this because many of them are my friends. The reason why this bears repeating is this: we tend to believe that Evil is the result of evil minds and morally degenerate people who want to oppress the masses, and while this is sometimes true, it is not always true. Sometimes, evil ideologies are born in the minds of the nicest people with the best of intentions. I believe that Hannah Arendt’s much misunderstood statement on the “banality of evil” was meant to puncture the myth of evil as being incarnated by some kind of monster. Evil can often take the face of banality and even the appearance of good.

Alta Ifland, June 2021