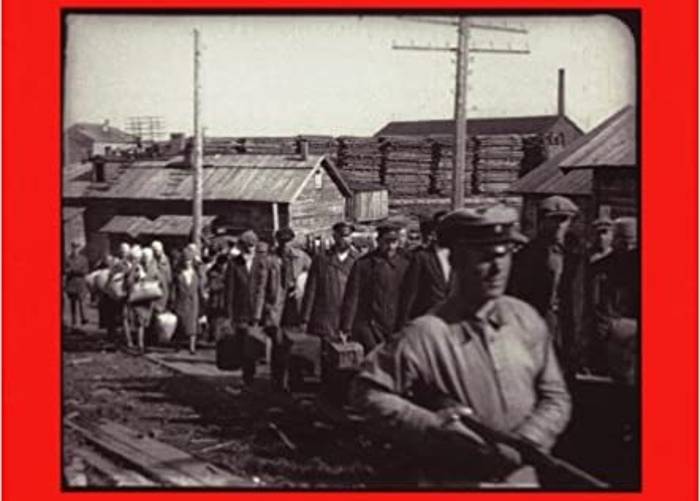

Casualties of this war cannot yet be counted. The Russian Federation invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022. For the first time since 1945, major Eastern European cities are being destroyed by shells and missiles not yet known in World War II. Thousands of people have already been killed. This includes hundreds of children who weren’t even able to cry before being killed.

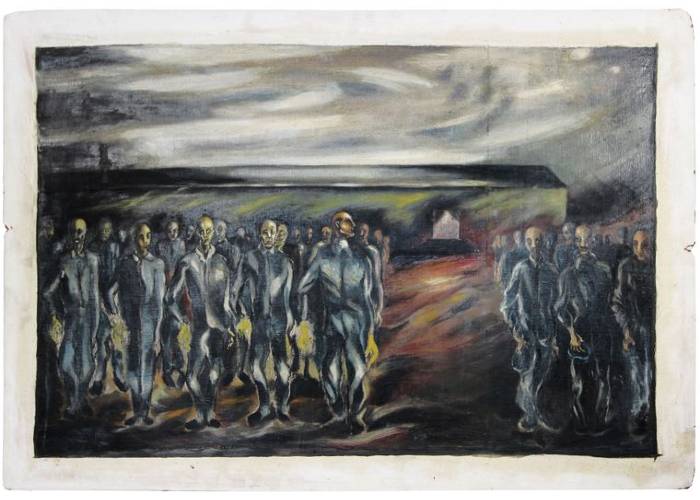

There are symbolic deaths. Among symbolic deaths, one can count the death of Boris Romanchenko, a 96-year-old former prisoner of Buchenwald, killed by Russian bombs in Kharkiv. “Denazification” was the name given to one of the goals of “the military operation” by Russian leaders. But it turned out to be, as usual, the opposite. Putin is completing the job started by the Nazis.

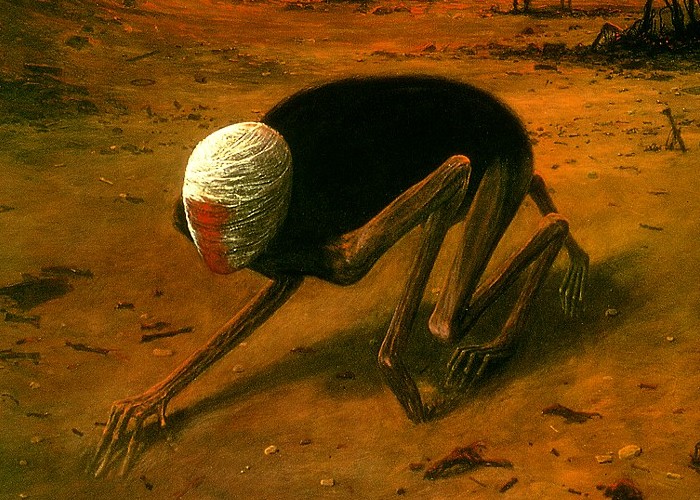

One should not expect any statements from the dead. All that’s left is mute stupor.

Yet, there are people who explain, in great detail, step by step, their demise in this war. We heard the most prominent voice from the realm of the dead on March 20, in mathematician Konstantin Olmezov’s Telegram channel. The text of this last letter from the native of Donetsk, who has lived in Moscow since 2018, will enter the history textbooks of this war. For us today, this document reads like a message from a man who has not yet departed into the realm of shadows. It is written as if the reader can either still prevent something or follow Konstantin Olmezov himself. The story he told before his death is much deeper than it might seem at first glance. And it is interpreted differently in Ukrainian and Russian sources. From 2014 to 2018, Konstantin lived in Russian-occupied Donetsk, and in 2018 he decided to continue his education in Moscow, at the famous Fiztech, where he was engaged in “science, which did not exist in Ukraine – additive combinatorics”.

In the first part of his letter, he says that he always thought that “Russian culture was at a higher level than Russian politics,” and this helped him tolerate the rather familiar Russian contempt for Ukrainianism as a not quite full-fledged version of Russian. But his main illusion – the ability of culture to defeat politics – was shattered on February 24, 2022.

On February 26, I tried to leave Russian territory. It was an act that was partly stupid, but only insofar as it was poorly planned. I don’t regret it, I only regret that I hadn’t done it on the 23rd when I had every reason to.

I was leaving to defend my country from those who wanted to take it away from me. To defend my president, whom I had chosen myself, feeling the same obligation a boss feels when defending a subordinate. By the way, I did not vote for Zelensky in the first round in 2019. And I wouldn’t have voted for him in 2023. But as much as I dislike him, what matters to me is the freedom of choice and the freedom to be responsible for that choice – responsibility to the point of fully experiencing the consequences of one’s decision. This is very difficult to explain to many Russians and pro-Russian Ukrainians – how violent changes from the outside, serving to improve well-being even across the board, can be unacceptable simply because they are violent and come from outside. It’s a little like trying to become free from one’s helicopter parents.

At this point, it is impossible to determine how many people had time to read all three of Konstantin Olmezov’s posts before he carried out his sentence. A scandal may arise around the Konstantin and the Bukovki channel, which now has three and a half thousand subscribers: the author describes his path to suicide in great detail and without any sentimentality.

But apparently, when all the texts have been posted online, they did not move anyone to contact the author at once and to convince him to start a new life in Austria, where some joint project was waiting for him. The author decided not to wait until the day he was supposed to fly to Istanbul.

I feel shame, thinking of my Ukrainian friends. Believe me, I never wished or did anything bad for Ukraine and I was always ready to leave, if the thing that we had all been expecting, were in fact to begin. Unfortunately, I just didn’t make it, I just didn’t know how to do it. The FSB agents who detained me talked to me as though I was a traitor, but on the morning of February 24, I felt betrayed myself. Yes, as ridiculous as it may be, but even though I recognized rationally and aloud that war was possible, emotionally it came to me as a shock, to a surprising degree. I had a naïve belief that juridical sensitivity in dealing with Ukrainians implied the possibility of an escape at a critical moment. I stuck my head too far down the tiger’s maw. This is my second big mistake, and I have a lot to pay for.

Now those who have already lost their homes in Mariupol, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, or Kyiv are fleeing Ukraine, as are those who are just afraid that specimen of the Russian world will get to their cities, such as Dnipropetrovsk or Odesa. And there are already almost three million such people as of March 23. The flow from Russia is much more modest – from three to five hundred thousand people: these are the people whom Konstantin Olmezov sees as undesirable neighbors in Moscow.

Konstantin confesses his love for the cultural monuments of Moscow and Kyiv.

Every shell that falls on the streets of Kyiv pains me. Reading the bulletins, I imagine the views of these streets, these districts. From the first day until now I have been with you with all my heart, although it is clear that I have not saved anybody…

Konstantin spent the first fifteen days of the war in an FSB cell where he experienced another disappointment – a loss of faith in his friends, who had worked in science and creative arts, many of whom decided to flee from Russia, although they were not threatened by bombing raids.

I am a complete atheist. I don’t believe in hell; I will go nowhere. But I prefer that nowhere to the reality in which many descend into savagery, while others indulge them in this descent, whether by throwing up their hands in a gleeful frenzy or by “evacuating” from the front lines. I don’t want to be with either of them.

Neither could he be with those who yell at the stadium for a bowl of buckwheat porridge nor with those who silently flee to the capitals of former Soviet republics. And now the phrase “I am partly ashamed of my Ukrainian friends” becomes clearer. Like many Russian-speaking Ukrainians, it seemed to Konstantin that after the occupation of Donbas his capital was no longer Kyiv, but Moscow. But in the few years he spent in pre-war Moscow, he began to feel, for the first time, that he was Ukrainian, or – in the eyes of his Russian colleagues – a second-class citizen.

When, in the twenty-first century, in the middle of the night, an army attacks a completely foreign country, a country that is not threatening it at all, and every soldier understands what he is doing yet pretends he doesn’t. …When that country’s official says “we didn’t attack” and the journalists amplify and spread this message. And every journalist understands that this is a lie, yet they pretend not to understand it. …When millions of people are watching this and understand that this will be on their conscience and their history and yet they pretend they had nothing to do with it. When black is called white and soft is called bitter, and it is not said in a conspiratorial whisper or with winking irony, but as though from the heart. When Zadornov’s joke about the American who said that “the Russians are cruel because they attacked the Swedes at Poltava” ceases to be a joke and is no longer about the Americans and the Swedes. When the world seriously discusses the possibility of what it has been trying to prevent for 75 years and does not discuss any new models of prevention. When force once again claims to be the main source of truth, betrayal and hypocrisy are the main sources of calm.

When all this is going on around me, I lose hope for a different way for humanity. I lose the desire to do anything for these people or with these people. I was aware that this kind of backslide would happen sooner or later, that the beast was incorrigible. But I had no idea that it would happen so soon and so easily, like the flip of a switch. Things that filled our lives before – can they have any meaning now?

Who would have thought that this would be the way the ancient genre of “conversations in the realm of the dead” would be revived in the new Russian world? And that with these words the victims of the war would bury their empire…

The original, in Russian, was published on March 22, 2022, in RFI.