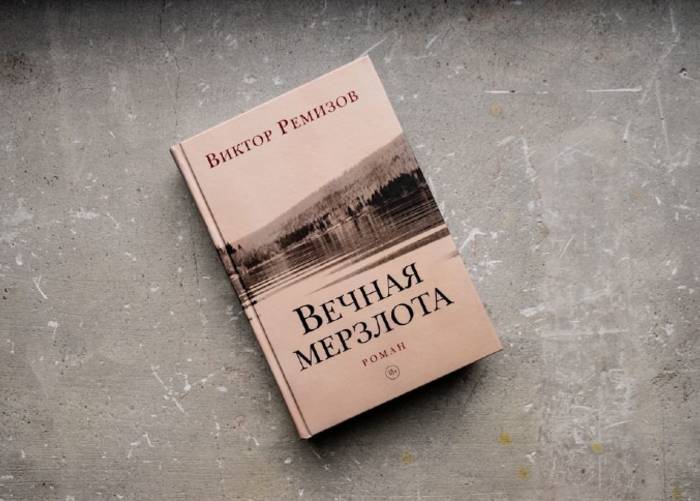

Viktor Remizov. Permafrost

Vladivostok: Rubezh, 2021.

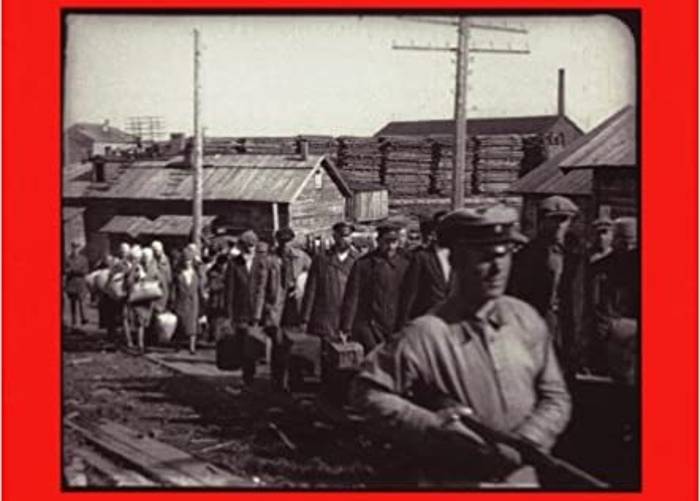

In the late 1980s, when the Stalinist terror was once again spoken of openly, it was expected that the society would be horrified and make every effort to safeguard itself against such threats in the future. But as we know, no strong condemnation followed, and as a result, the society failed to establish control over its own power and became utterly confused about what was right and what was wrong, about what was acceptable and what was not. Now, 30 years after the collapse of the USSR and 65 years after the 20th Congress, there is no longer any demand for cleansing and defending ourselves from the past but rather a demand for a so-called reconciliation with it. Attempts at such reconciliation are expressed in several popular ideas: there were no so many victims of terror and, for the most part, the Soviet people lived quite happily; not all victims were innocent, many were punished for their actions; people paid a high price, but they built an industrially developed country; the time was cruel, etc. In literature, this trend has manifested itself in a number of works that offer the public their own versions of consolation. We’ve seen works that seemed to say what a great idea was the education of the new man and how interesting and strong were the people who embodied it (“The Abode”). Then there is also the theme of guilt, which allegedly lay on the victims of repression themselves and insistently demanded redemption (“The Aviator”). Or the depiction of the terrible life in exile as only a continuation of the no less terrible life in a patriarchal home (“Zuleiha…”). The old-fashioned tale of “love that overcomes all obstacles” also plays a significant role in creating a comfortable myth of the past. A love between a camp guard and a Chekist in “The Abode” secured an indestructible national unity, while the mother’s love for her son in “Zuleikha…” paved the road to freedom. So, on the whole, the picture of the Stalinist years turns out to seem not at all hopeless. The recently released novel by Viktor Remizov “Eternal Permafrost” is a book from a completely different bookshelf. Here the author leaves no room for bright spots, pleasant delusions or unobtrusive sidestepping.

One by one, Viktor Remizov destroys the bastions that have become entrenched. The first of these is the notion that Stalin’s power was rational and effective, albeit extremely rigid. All events in the novel unfold against the backdrop of the grandiose construction of the Great Stalinist highway: “a thousand and a half kilometers of railroad had to be constructed along the Arctic Circle, connecting the Northern Urals to the lower reaches of the Yenisei. All resources, all the darkness of the construction materials, equipment, food, people, convoy for people and supervisors over people were scheduled by the national economic plans by year, allocated and moved, flocked from all over the country to the destination.” Prisoners were used as labor. The construction project was a colossal undertaking and managed to eat up a huge share of resources and funds. But pursuit of ostentatiousness led to the fact that the construction began to turn into a Potemkin village, built personally for the leader: “The ribbons were cut, hurrahs shouted, hats in the air, report to Moscow: the first kilometers were laid on the unmade taiga! Swamps frozen, and the highway was laid on top of them! And no planner would ever dare to tell the truth.” Immediately after the death of the dictator, the construction was first mothballed, and then completely stopped and abandoned. The picture is very clear: the system of management of the country under a dictatorial regime is set up to achieve a single goal, which is to please the tyrant, and this task becomes the imitation of success. As for the rationalization of the OGPU – NKVD – MGB and Stalin’s internal policy, the author depicts it on two levels – the state one and the personal one. An employee of the NKVD speaks on behalf of the state. His thesis is quite well known and popular: in Russia any other way is impossible. Stalin “had to run a huge country! Full of uneducated people who didn’t know or have any self-discipline! Or, who didn’t know what it meant to be responsible for their own behavior! A country envious of others’ wealth, lazy, living in filth and starving, without any knowledge of high culture! How could it be ruled? Only by fear! For centuries the master ruled his peasants with a birch branch, and the Russian peasant knew nothing else and did not want to understand anything else! … The master, like an experienced doctor, administered pinpoint doses of fear! Now in one department, now in another! Small doses, so they would not be forgotten!” According to the same intelligence officer, such a system is based not so much on punitive measures, as on the willingness of the majority to sacrifice the minority “for the common good. Such an understanding of things, a reliance on savagery and backwardness, produces a fatal vicious circle: the country, which was not really acquainted with the rule of law before and is once again ruled by brute force and fear, does not develop, but sinks deeper and deeper into lawlessness.

At the personal level, the implementation of this attitude is described in detail in the depiction of two main characters – a geologist Georgi Gorchakov, who is serving a 25-year sentence, and a young Yenisei captain Alexander Belov. In fact, these are the people who, in the opinion of the MGB officer, can be controlled only by birching. Gorchakov is a former honored geologist, а PhD, but by the time the naarative begins, he is already a former convict, a broken man, who has long ago given up on himself. His family –wife and two sons–is left behind in Moscow. Certain that he will never be released again, Gorchakov decides to break off all ties with his family and writes a letter to his wife asking her to forget about him and marry another man if possible. Gorchakov, who has been convicted three times, received his first sentence when it was decided at the top that geologists, developers of ore deposits in Norilsk, who had been considered heroes of labor and the vanguard of the builders of Communism, must get their portion of fear. A group of “saboteurs” was chosen quite arbitrarily, and within this group, the “initiators” and “executors” were appointed just as arbitrarily, and then, like in a lottery, sentences were handed out – from 10-year sentences in the GULAG to capital punishment. Gorchakov tells about it to Belov in a confidential talk: “At the trial they called me a member of a fascist terrorist organization and accused me of sabotage for concealing mineral deposits. The whole accusation was based on a testimony of one man whom we didn’t even know. He incriminated a lot of people, and at the confrontation meeting he could neither speak nor stand, he just nodded and shook all over – it was a scary sight. … My trial took less than ten minutes. … I got a ten year sentence, while nine people out of sixteen were shot. Those who had been shot were no different from those who had been sentenced, and I don’t know why they were killed …”. Life or death: heads or tails.

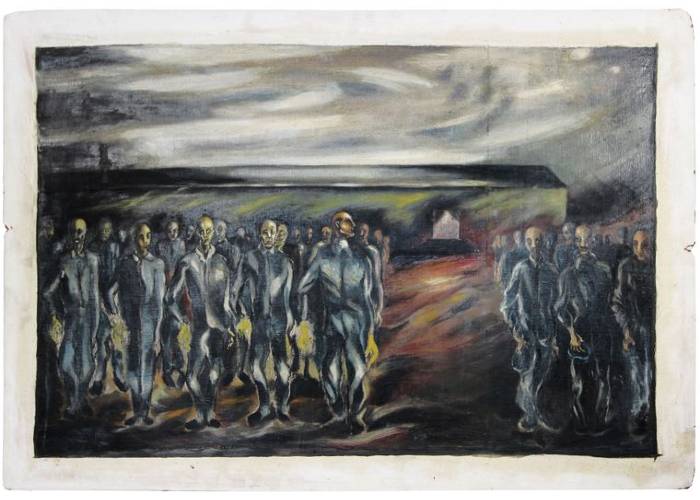

But the heaviest burden in the novel falls on the shoulders of the second main character – the captain of the river tug San Sanych Belov. Two key themes of the book are associated with him. First, his experience shows the reader the price of fatal errors and of an unwillingness to admit the obvious. Working on the Yenisei, meeting prisoners and exiles, and knowing their life stories, the straightforward and naive captain Belov, nevertheless, remains a faithful Stalinist for quite a long time, believing in the genius of the leader and in the greatness of his goals. Everything changes when he finds himself in prison, where he is inhumanely humiliated and tortured, coerced to confess to participating in an invented conspiracy and forced to testify against his close and distant acquaintances. “Permafrost” is a difficult read. The author immerses the reader in the reality he has recreated and slowly takes the reader through all the circles of hell, through interrogations, taunts, threats, beatings and inquisitorial torture, giving us a clear understanding of how a living person subjected to all this must have changed inside. And most importantly, the writer does not let us forget that the interrogations, torture and abuse had no purpose other than large-scale falsification. Once a request from the highest levels of the government to expose major conspiracies comes through, the authorities hastily inflate yet another huge empty bubble-simulacrum: empty, yet devouring.

One of the elements of the story of Captain Belov is the archetypal Faustian plot, which does a good job of making sense of real life in Stalinist times. Belov refuses to make a deal with the devil, that is, to cooperate with the authorities as a snitch. This refusal makes him the object of a particularly cruel and vindictive persecution. It is most significant that he comes to the refusal through the initial consent, dictated by the same naivety and unwillingness to recognize black as black. He is caught in the net unbeknownst to himself. There is no distinct moment of choice in his life. It is much later in the novel that he is faced with the choice between playing the role of a snitch and imminent death, and by that time he is already completely in the clutches of a devil. In this novel, a human being faced with evil can’t see the whole picture and is not aware of what he is dealing with, and this makes his situation even more terrible and dangerous. Victor Remizov’s heroes often find themselves in absolutely hopeless situations, when there is no greater or lesser evil, because the total hopelessness of evil surrounds them on all sides.

Now about the saving power of love. Gorchakov’s wife and children are left behind in Moscow. Belov falls in love with Nicole, a Frenchwoman, who happened to be among in a group of exiles from the Baltics through a misunderstanding. Both women are portrayed as having true love, inhuman fortitude and heroic determination. Yet both love stories in this novel end up tragically. From a long series of upheavals, losses and misfortunes, all the protagonists, men and women, emerge so broken, exhausted and crippled that it is impossible for love to overcome it all. Instead of a reassuring triumph of love over grief and death, the reader sees a total triumph of evil and stubborn absurdity over normal life.

The novel is set in the last years of Stalinism. From our current point of view, people should have been relieved as the period of terror comes to an end. In the novel, however, we see that every day of the dictatorship cost more lives. One of the final episodes of the novel is a bloody suppression of a purported rebellion in one of the camps: “And then the machine guns rumbled. Gorchakov shuddered in surprise. Chips flew from walls of camp barracks, windows tinkled and crumbled. They were shooting from towers and roofs of the guard battalion houses… Machine guns easily penetrated walls; people could not hide.” So no, it did not get any easier. Tyranny is a disease that can only get worse.

How is a fate of an “enemy of the people” portrayed in the novel? A person who is not only totally innocent of any crime, but greatly honored in his profession; a person whose contribution to science was useful and important, is snatched from his normal life with claws of iron and sent to a torture chamber. There he is beaten until he gives them what they want–the needed confession of his own guilt as well as a testimony against someone he knows or even people he does not know at all: a chain of terror must not be broken. His family members, even if they remain at large, are also enemies now, with all the ensuing consequences. If the accused is lucky, then, after going through more torture and a “trial”, he is given a sentence of many years in prison instead of a shot in the back of his head. Yet the conditions of the imprisonment are such that the living are sometimes jealous of the dead.

What is such a person’s posthumous fate, what do his descendants say and think of him? Even his descendants tend to treat with suspicion or turn away or just fail to notice him, quite sincerely. For the sake of their own peace of mind and for the preservation of a positive picture of the world, new generations continue to lie to themselves about the past. But this is a problem of the new generations. One day their glimpse of the past may turn out to be a glimplse of their own future, and then it’s all up to luck. Heads or tails.

Translated from Russian by East West Literary Forum

The original of this article was published in “Druzhba narodov” (August 2021 issue). The translation is published for the first time.