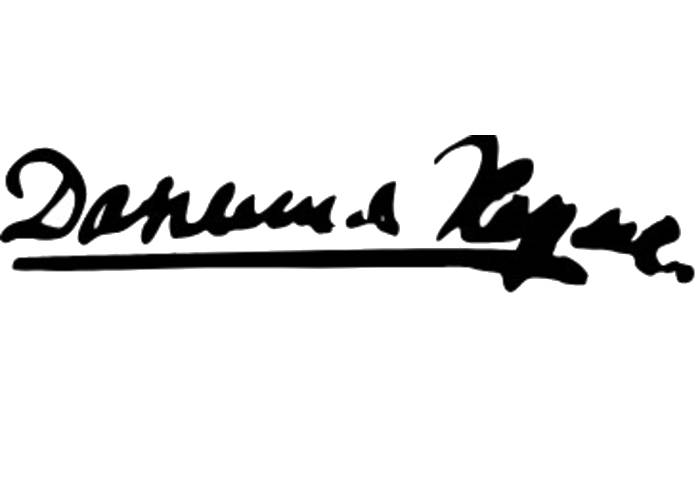

It is well known that Kharms shrouded many facts of his birth in mystery. But thanks to the Bolsheviks, the location of the great Soviet writer’s death cannot be questioned. Any schoolchild will tell you that Daniil Kharms died of hunger in Leningrad, in a prison’s psychiatric ward, during the Leningrad Blockade. The writer first successfully portrayed madness in 1939 and received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. However, there is a special category of madmen that is very difficult to recognize. We’re talking about those who “play sick,” for there is much to suggest that Kharms was a madman feigning madness.

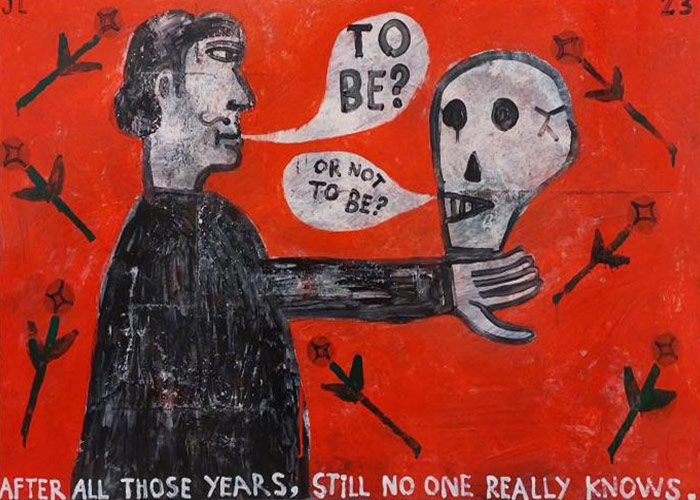

Let’s begin with a quote from Kharms himself: “When Pushkin broke his legs, he began to move around on wheels. His friends loved to tease Pushkin and grab him by his wheelchair. Pushkin became angry and wrote abusive poems about his friends. He called these poems erpiharmas”. At first glance, it seems that the evidence for madness here is only circumstantial, hidden in the license of the written content. But no, upon closer examination, “er” means “erratic”—inconstant, insane. “Pi” is clearly associated with the number π (Pi), which is infinite and irrational, being a symbol of chaos and madness. “Harms” is obviously “karma” or “harmony”. If harmony is broken, what remains is its broken form of disharmony and madness. But Kharms is more brilliant! He doesn’t hide his sexuality! His diary is replete with mentions of fellatio, which Kharms constantly craves and seeks, obviously considering a daily dose of it to be the norm… He clearly had a hard time in prison.

But let’s return briefly to Pushkin and the erpiharmas… “Er” is a clear echo of Eros (ἔρως), transforming the number Pi into infinity, as befits an immortal god. “Harmony” remains here as well. Incidentally, as is widely known, in the ancient tradition (see Plato, “Phaedrus,”) Eros himself was interpreted as the manifestation of divine madness (μανία ἐρωτική). Anyone would agree that the attraction of love is already a form of madness, “obsession”. Thus, erpiharma can be interpreted as a mad passion, where harmony is distorted by the irrational infinity of desire. Erpiharma is a state where Eros develops into mania: love turns into madness, logic collapses, the harmony of passions is destroyed, and all existence becomes “an irrational verse of desire”

I can’t help but admit that several years ago I bought Daniil Kharms’s tablespoon at an auction. Here it rests before me on a velvet cushion—heavy, cool to the touch (I picked it up), made of solid silver with a subtle, slightly darkened sheen. The metal has long since lost its factory shine, but has acquired a different one—deep, soft, as if glowing from within. On the handle is an elegant engraving, created by the hand of a master: Art Nouveau curls, wafting and yet meticulous, like an arabesque. On the back are barely discernible initials in Cyrillic—ДХ (DKh). The bowl of the spoon is large, oval, with a slight asymmetrical curve—a style used in the early 20th century to help food glide off more smoothly. I imagine Kharms’s long, thin, and almost transparent fingers holding this spoon, which I now grip tightly so I may attempt to tap into the energy of this unique writer.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist a rather seditious thought—did Daniil scratch his shameful parts with this very spoon? It’s easy to imagine the boundlessly talented writer lounging on the sofa, wearing a dark gray coat over his bare body, his hairless, sunken chest glistening, his woolen pants resting loosely against his stomach, so that it wouldn’t be difficult for Daniil, lost in his dreams (about what? about fellatio?), to slip past the waistband. However, one could also imagine a sizzling white boiled egg on this spoon.

I don’t want to admit to you what I just wished for… Kharms positively has a negative effect on me; I feel as I did in my childhood—a thug… no… long ago, I had thoroughly squeezed “the slave” out of myself and scrupulously scraped out “a thief.” In real life, Kharms couldn’t hurt a mosquito… If we assume for a moment that any writer is capable of writing only about himself, then metaphorically Kharms’s legs were broken, and he felt like an invalid in an imaginary wheelchair.

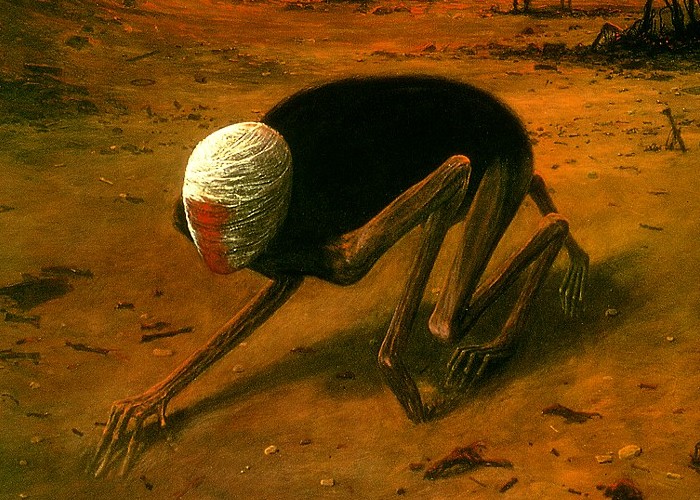

Daniil Kharms misperceived his madness as a moral deformity, carefully concealed in madness and regenerated in prose through an attack on form and content, in the best tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche would certainly have considered a sunken, hairless chest a sign of spiritual exhaustion and an indication of excess, for the body, stripped of flesh, acquires the lightness of the transcendental. In this naked concavity, the German philosopher would likely have seen both a collapse and an ascent, a fracture from which the path to great heights is born, and where he would have discerned the dance of the spirit, freed from heaviness, twirling like a mad acrobat on a tightrope stretched between emptiness and eternity.

After all, Tolstoy, analyzing “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” considered Nietzsche mad. In his own words: “I became fully convinced that he was completely mad when he wrote, and mad not in the metaphorical sense, but in the direct, most accurate sense: incoherence, jumping from one thought to another, making comparisons without indicating what is being compared, beginning thoughts without an ending, jumping from one thought to another through contrast or concordance, and all against the background of the point of madness —the idée fixe that, by denying all the higher foundations of human life and thought, he proves his superhuman genius”. We find exactly the same in Kharms, but the genre of the absurd, being a literary reflection of madness—unlike the genre of philosophy—easily accommodates the whims of the greatest taunter…

And yet, I cannot resist fulfilling my seditious desire—to slide the hard handle of the tablespoon under my belt, and the less said the better… What is most important is that I feel an upsurge of strength, my thoughts flow like a turbulent river, my words seethe and stir. It is painful to think that as a child, Kharms endured such severe abuse that his gentle psyche couldn’t withstand it. Some cruel children can laugh at a boy in a wheelchair. Some heartless kids can tease a little boy and grab him by that wheelchair, as if he were some kind of a growing thing… that needs to be poured out onto paper. Even a chaste schoolboy understands that the pain of his chafing childhood experience was translated into the wordless language of Eros. And that, judging from his diaries, instead of writing abusive poems, Daniil was in a constant search of daily fellatio… Surely, playing the madman added a lot of charm to Kharms, creating—in his case—a special mixture of childish spontaneity and demonic stubbornness.

I apologize for the essay’s rambling and its vulgarity, with its cloying reference to fellatio, which haunted Kharms’s mind, especially in the psychiatric ward of a Leningrad prison during the Leningrad Blockade, when he was dizzy from hunger and slumped on his bunk in his now-familiar coat and trousers, a blissful smile on his face, his eyes closed. He was certain everything was going according to plan and that he was mastering the art of feigning insanity.

Translated from Russian by Elena Livingstone-Ross