I enter my house in which I was not born,

where I never lived and never will,

but I remember things I never knew,

and realize things I don’t remember since

I know that I lived here before I was born

in my father’s childhood and in a foreign tongue.

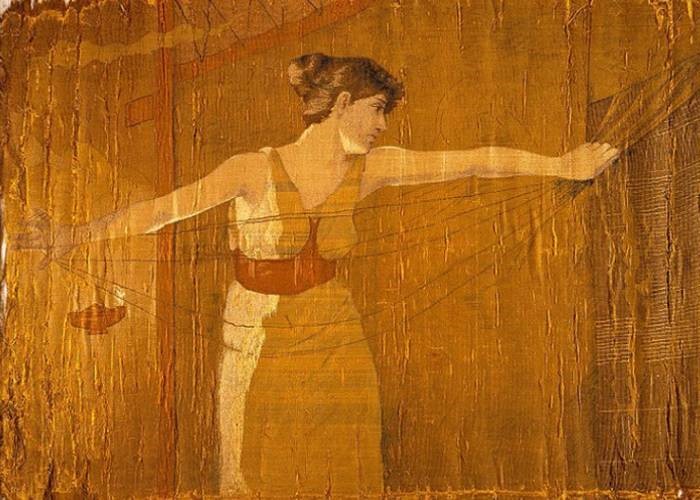

Here is my father’s mother (whom I cannot,

for the life of me, call my granny, as I never met her),

goes to the market, a strange stranger,

down the Słowacki Street, while the clock

on the tower brings the time closer

when down the same street but uphill

my father returns from the gymnasium,

bypassing the synagogue, which

is now the public library, but —

is this lanky boy my father? –

he is now my son already,

upset with a grade, a B, because

his teacher told him that a Jew

could not master Polish: it was easier

for a monkey to become human, – but enough,

enough, don’t cry, my boy, calm down:

you and I have mastered quite a few languages

in the last two thousand years,

we had been led away from God by our knowledge

and mixed among the nations and the tongues

(in my own time, I would be told by the scribes,

that the Russian tongue was spoiled by the Jews)…

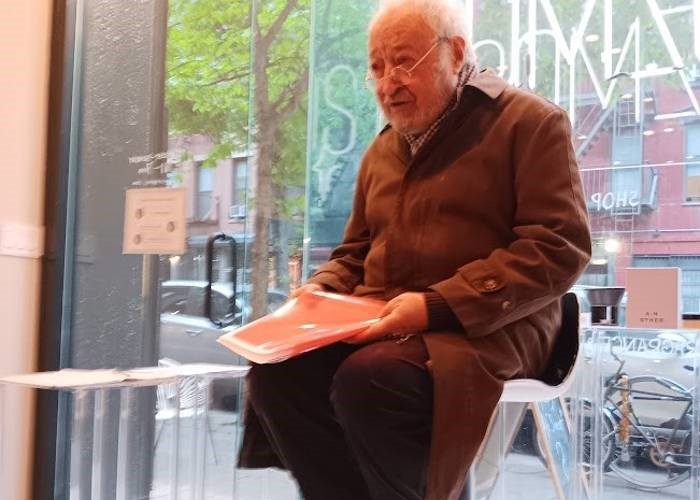

So enter the house: the owner, Leo Gottfried,

has by some miracle escaped (he’s now in New York);

so enter the apartment (“parter” means ground floor)

and knock timidly: “May I see you, tatus?” *

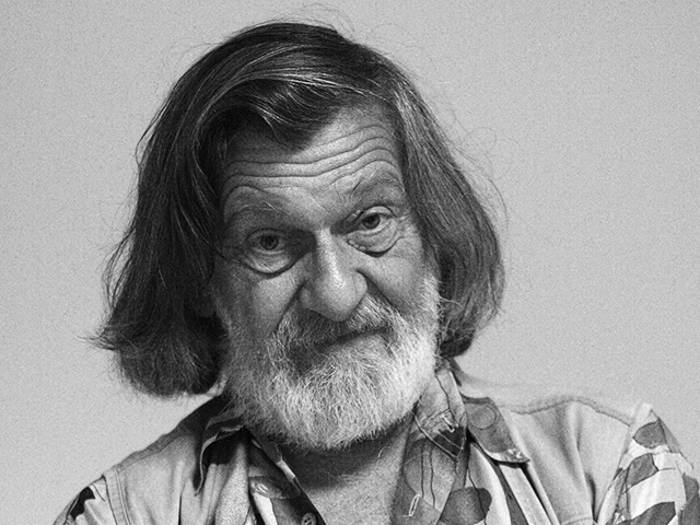

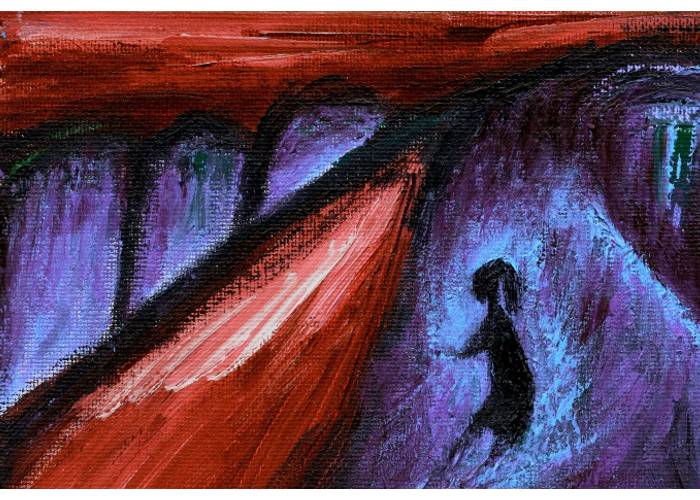

and pulling your grandfather away from his easel,

pour out to him that first offense,

and he will comfort you, your executed father

(till your own death you’ll be talking with him

and in your sleep will sing “El Maleh Rahamim”).

So enter bravely: this is your father’s home.

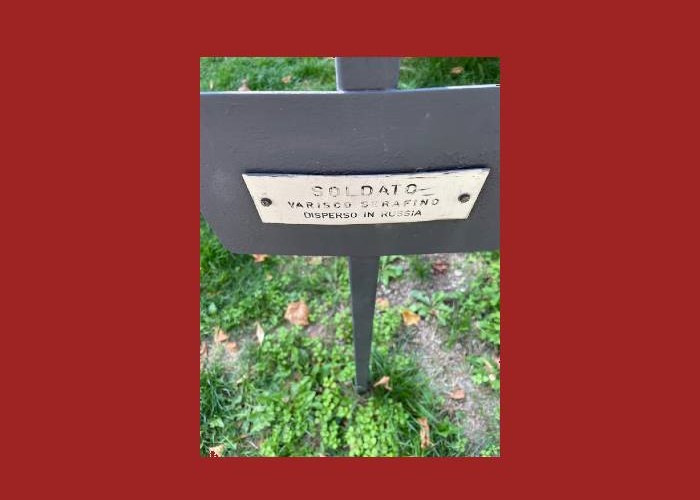

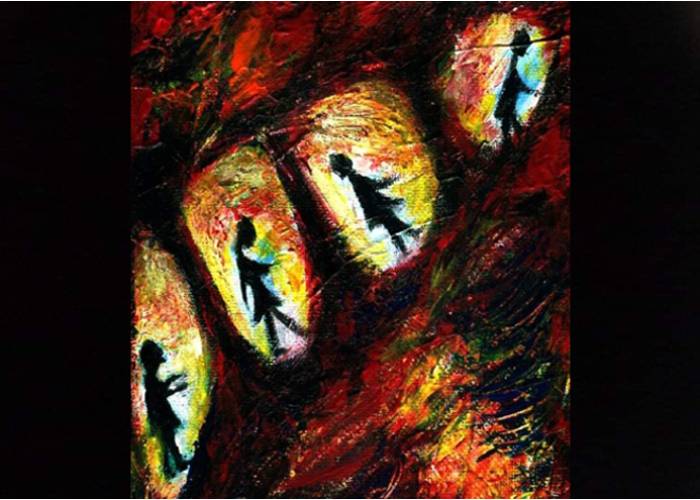

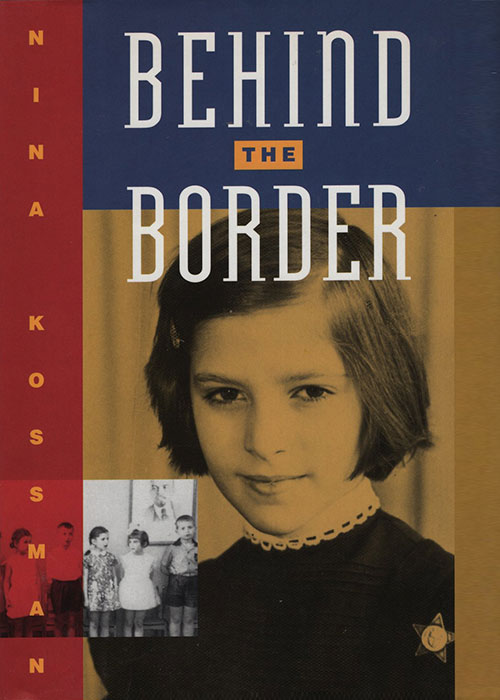

Then, when those who hadn’t been shot in the first month,

would be sent to the ghetto, their apartments

and houses that had belonged to the Jews

will be taken over by neighbors who will split the stuff,

and, at twenty-three years old, you will come home,

wounded, and a liberator,

but the new owners in nineteen forty-five

won’t let you – a stranger – in,

and knowing that all your family has perished,

you’ll leave, slamming the border like a door.

You’ll find yourself in Russia, not knowing

that while you were fighting for Warsaw,

Stalin and Hitler divvied up your city

(the only witness, was the stony San,

a boundary between death and dishonor).

And I was there too and I did meet those Jews

in the overgrown cemetery where the trees,

with their roots, pull out headstones,

where a cenotaph to four thousand slaughtered Jews

stands on a patch in the middle of desolation.

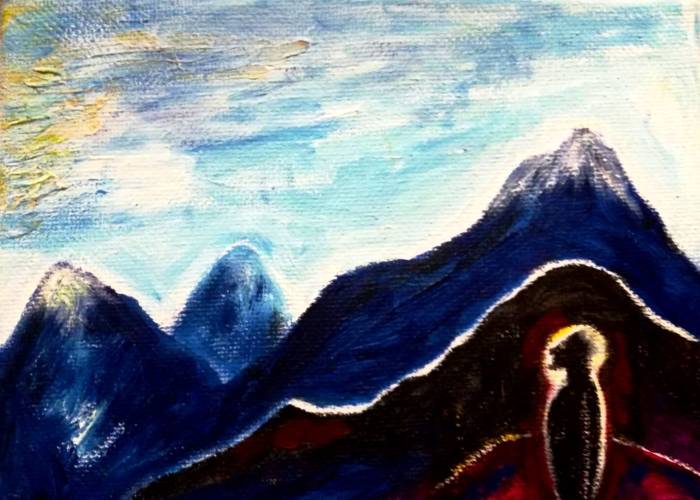

The beautiful city is running up into the hills, —

cleansed of filth: Judenrein.

The apartment is divided into cells,

five families crowd in one wing. No one

remembers my grandfather. Amnesia.

In that town of oblivion

six old Jews remained, the rest

of the survivors left, never to return…

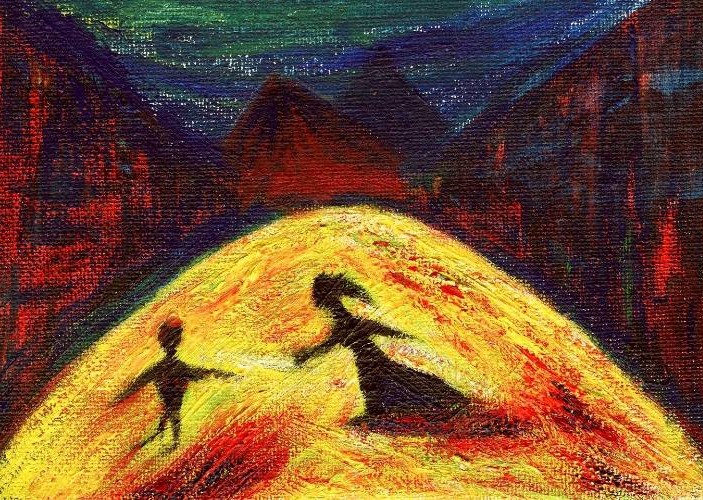

Could it be that God Himself was powerless, or

was He the One who had led the six million

along the path of concentration camps

and pointed the way to salvation through

the Auschwitz chimneys? I do believe:

the world will be saved from the Flood

and amnesia by remembering Hiroshima,

Afghanistan and the small Chornobyl,

when a six-winged dove flies in with a weird twig

and perches on an Auschwitz chimney.

1988

* Tatus’ (Polish) – daddy

Translated from Russian by Nina Kossman