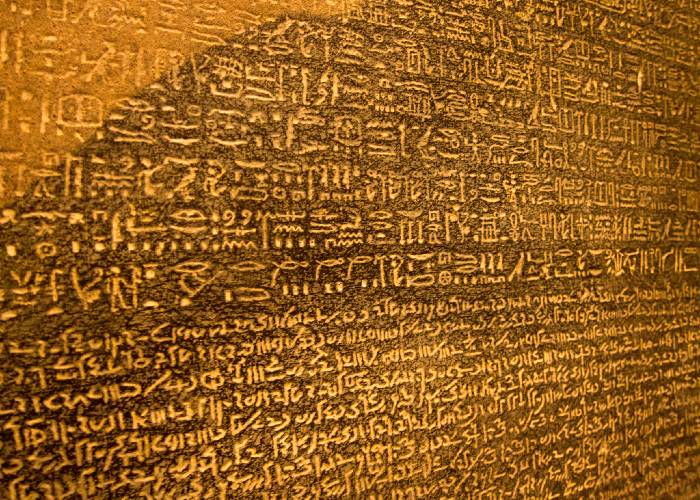

The main Russian concepts describing human mental activity employ words of Greek origin. This knowledge is sometimes sufficient to ask the Greeks how they learned the truth. Knowledge in general is a temporary concept. First, it is impossible without a memory of the past. Second, it is only achievable for those who can distinguish between “before” and “after.” In other words, cognition requires a firm belief that the past existed and that the cognizer remembers something vital about it. But here we—and the ancient Greeks!—are faced with the following difficulty. The ancient Greeks believed that time itself did not immediately arise from Chaos. First, they thought, space formed between heaven and earth, from which what we now call time was born. No sooner had it been born than time began to deal quite harshly with its own creations.

You don’t need to be an expert in Greek mythology to understand how true this is in our everyday lives. Time seems to devour us, leaving us not a shred of our own past. Yes, it allows us to remember, and the Greeks even had a special goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, whose daughters, the famous Muses, taught humans various clever mnemonic devices—musical instruments and how to play them, writing comedies and tragedies, as well as historical works and political treatises. But this is not the past itself, only a pale image of it. We change irrevocably and sometimes forget what we thought we knew by heart, having experienced it ourselves.

What are we to do? After all, the past is such a convenient thing for the purpose of knowledge—for establishing the truth! Do all disagreements and enmities really begin with the disappearance of a common picture of the past? One person says the words “war” and “ruin,” and the year 1941 or 1950 comes to mind. Another says “war” and “ruin,” and his memory conjures up, for example, the turbulent 1990s. For a third person, 2012 is still a peaceful time, but 2014 is already a year of war. After all, people can never agree on a common truth. What to do? How can we seek this truth through joint efforts?

The Greeks gave us two ways of establishing truth, which we continue to live by. We call one the Greek word “myth” and the other the Greek word “logos.” One cannot exist without the other.

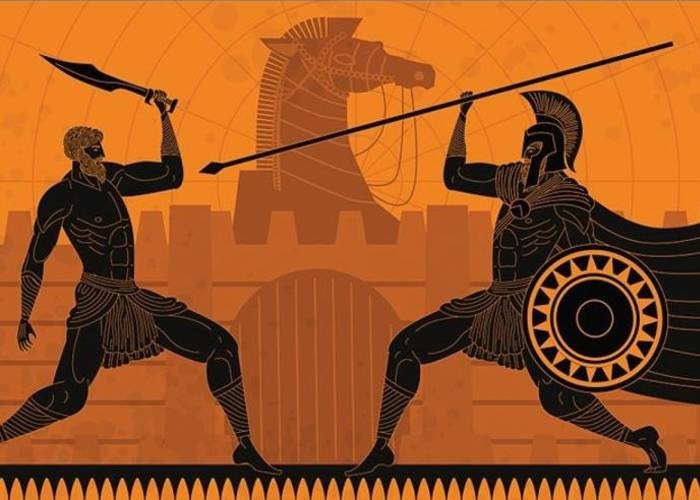

Most people like the mythical way of knowing because it is entertaining. To use myth to establish truth, one must agree on eternity, or that somewhere on some tablets, in one way or another, all moves have already been recorded. Thanks to this agreement, the institution of oracles, prophets, and fortune tellers worked very well for the Greeks. This institution kept even the gods in fear for several thousand years. In fact, it exposed the main secret of the supreme deity, Zeus: his incomparable cowardice. Zeus had many affairs with both mortal and divine women. But once in a while, the oracle informed him that a boy born from this or that union would take his throne. And then Zeus, in fear, either ate his beloved (so instead of a son, he gave birth to Athena from his own head), or slipped her a simpler husband. From such a union, the formidable Achilles, hero of the Trojan War, was once born. And with the Trojan War began the history of all other wars.

It began, as we can see, with the fear and vanity of the supreme deity, and then other accompanying causes were added—greed, lust, envy, and resentment.

All these stories can be told endlessly. But the essence of the myth is always expressed by the formula: all this was foretold, and only those who can coherently and convincingly recount how, day after day and year after year, events unfolded that could not be avoided, will know and understand it.

As we can see, myths require seekers of truth to have mutual trust, a good memory, and a willingness to admit that time is a big circle, like the familiar cycles of the day, week, year, and entire life. We often use expressions such as “it was written in the stars.” This mythical view of life does not mean that people are willing to deceive themselves. It only means that it is easier for ordinary people to believe in something predetermined than to force themselves to think about the connection between the past and the present.

The Greeks believed that only a great hero or king could challenge his own destiny, even if he had received precise knowledge of the future from an oracle. Such were King Oedipus, Prometheus, and Hercules—the very gods and heroes whose names are associated throughout Europe and its cultural heirs, from America to Australia, with great misfortunes arising from knowledge of the truth.

Myth is a long, long familiar story about how everything really was.

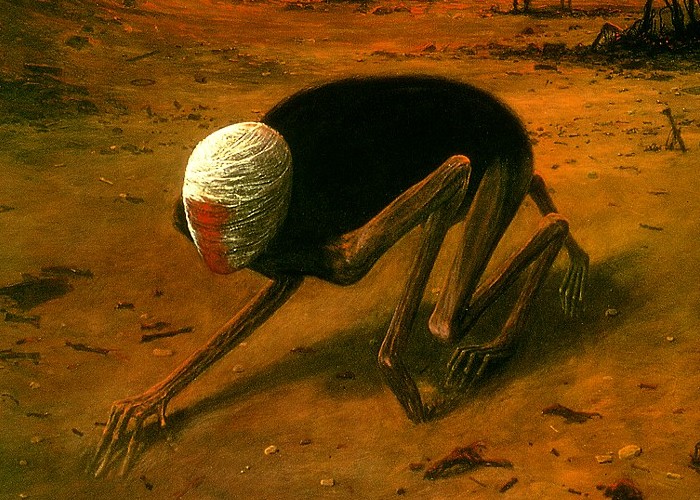

But this story, the Greeks believed, was not enough. If you leave a person alone with a myth, he will spend his whole life—and here’s another Greek word!—fantasizing. Fantasy is beautiful when it comes from the brush of an artist or the chisel of a sculptor. But what can you do when, following the example of well-known myths, people begin not only to create their own dream worlds, but also force others to live in them with them?

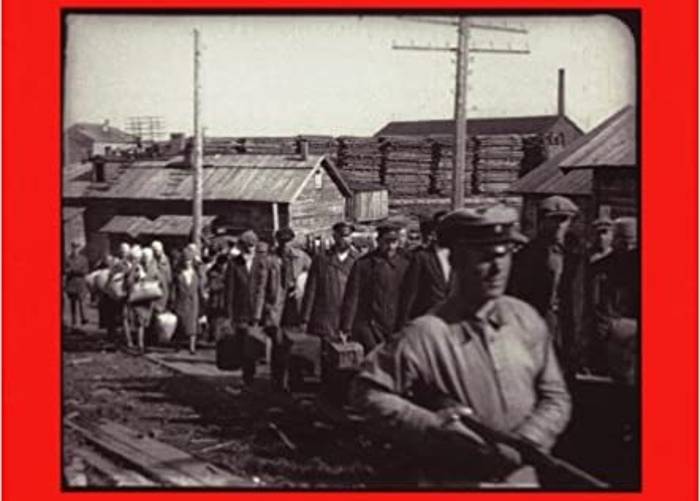

In his short treatise on memory and recollection, Aristotle recalls the madman Antipheron, who saw ghosts everywhere and fought them, demanding that others join him in this war.

Why was Antipheron’s complex so terribly contagious? It easily takes hold of the minds of those who know little and vaguely remember what an authoritative but malicious person can point out to them. To protect people from the substitution of truth by deceptive collective fantasy, Aristotle says, a counterweight to myth is needed—logic. But myths are understood in passing; they are interesting to retell and interpret, whereas the rules of logic must be explicitly learned. That is why rulers who want to stay in power for as long as possible dislike logic so much and are so eager to replace syllogistics with deceptive, phantasmagorical, immediate feelings.

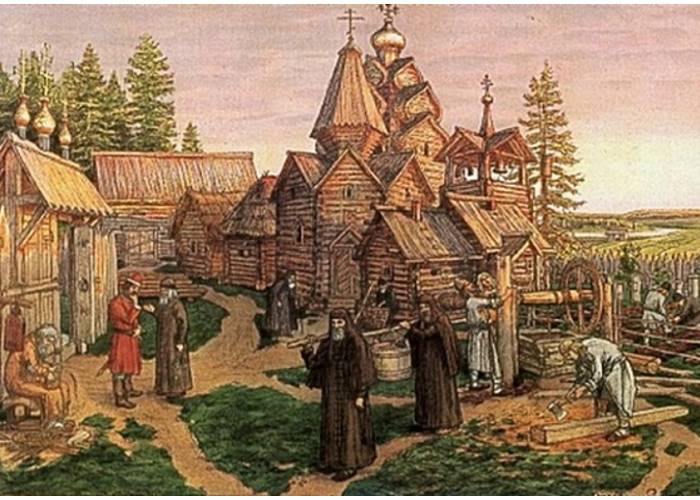

For example, Soviet life was monotonously red. The primary color of the calendar and life in the late 1980s was replaced in Russia by the three colors of the new state flag, borrowed at the time from the Dutch. In Ukraine, it was yellow and blue; in Armenia, orange; and in Estonia, blue, white, and black. This explosion of colors appealed to the memory of a few, but for the majority, it was supposed to give rise to new feelings and revive old myths of statehood. Incidentally, the rainbow flag of the movement for the equality of so-called sexual minorities also found its way into Russia. It became clear to many that this rainbow was not only sexual but also political. Behind the numerous national myths and flags of different countries lies a whole tapestry of history.

This colorful emblem is fine when playing soccer or choosing a country flag instead of a faceless number to dial on Skype. But what do you do when you need to create a myth in a matter of hours? How do you quickly show them the whole truth about themselves in a single symbol and immediately rally them behind you as your loyal followers?

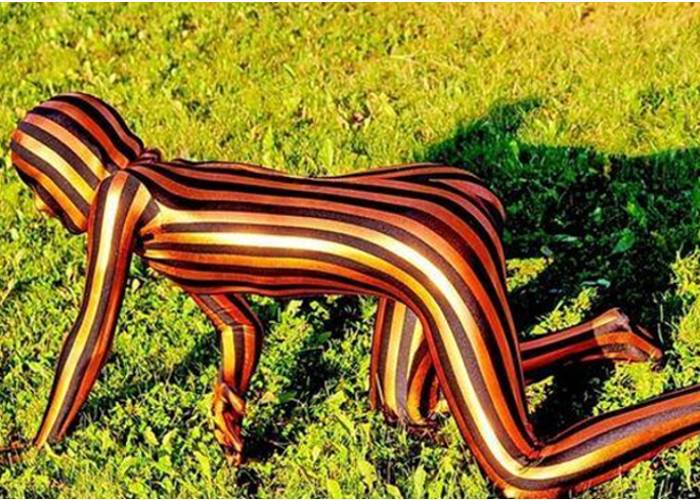

Like Aristotle’s Antiphon with his ghost, our contemporary begins to draw new flags, passing them off as very ancient, original, and authentic. Last week, the flurry of colorful stripes and crosses of “Novorossiya” finally infected even the most concerned parliamentarians. Apparently envying the beauty of foreign banners and despising his national flag as an emblem of dangerous Dutch disease, a deputy proposed replacing the white-red-blue tricolor with the so-called “imperial flag” — also a tricolor. Even though it is younger than the current tricolor and was only in use in the Russian Empire for a few years in the second half of the 19th century, there is still a desire to use this old-new tricolor as soon as possible—as an infallible weapon of truth about Russia—a country of purity and spirituality (white), holiness and Byzantine tradition (gold), state power and loyalty to the motherland (black).

Sometimes people are driven or bring themselves to such a state that they can be lured or driven away with a colored rag. A human bull can be a perfectly normal person in everyday life. But a colorful rag suddenly excites him. And he starts to act like a bull. Why? Because for him it is a sign of a vague memory of something he cannot remember himself, a myth, but a myth so close, so dear, that it is strange how others do not want to share it with him.

The world of fantasy seems so ancient, so undeservedly forgotten. You have sacrificed dozens or even hundreds of people to this world, people who had no idea not only of your madness, but even of your existence…

And now the day has come when the truth has been revealed to you in its most terrifying form.

All these sacrifices are in vain. And now there are no other people, and you are here with your madness in your multi-striped patches and banners. Like King Oedipus with his eyes gouged out, like Hercules in his burning cloak. The myth — you know it — will burn you to the ground. If only you knew logic, if only you understood why this happened to you, why the truth is such a pain.