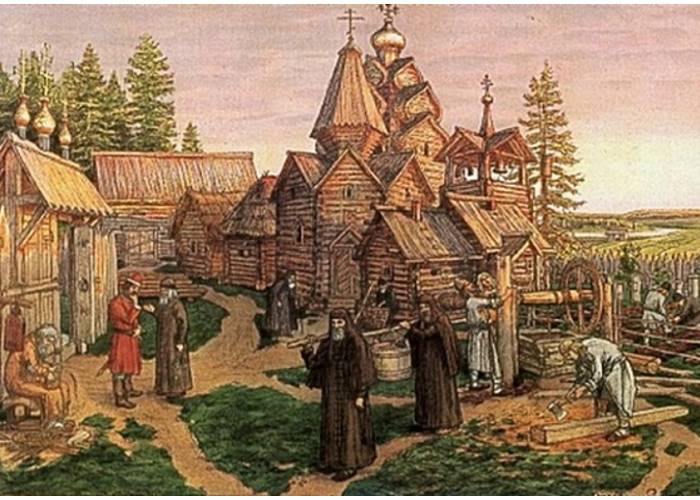

Vladimir Mayakovsky, the son of a forester, grew up in the wooded mountains of the Caucasus. Chaim Bialik spent his childhood in the forests of Volhynia. Viktor Khlebnikov grew up on the edge of the Kalmyk steppes. Nature became their first school and their first metaphor—an image of the world speaking through trees.

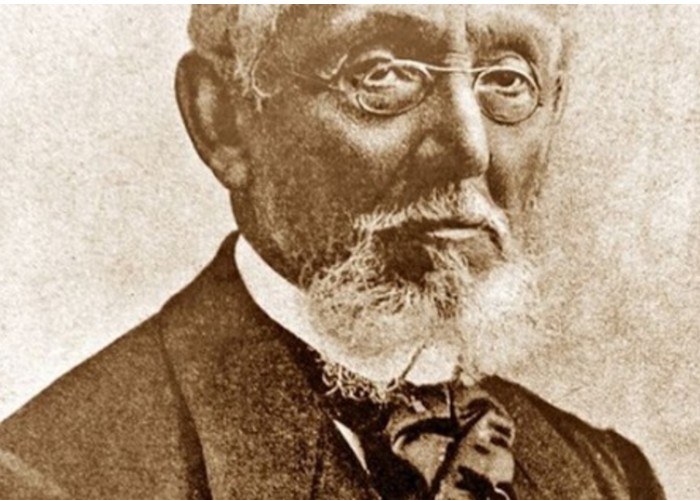

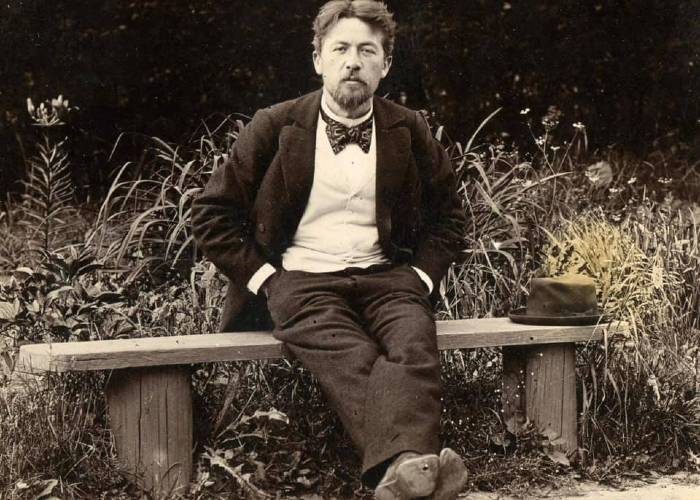

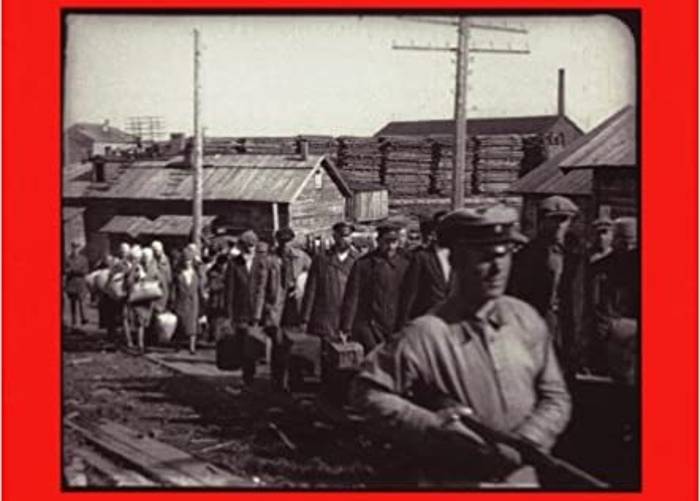

Their youth took them from these places to the centers of the era. Mayakovsky went from the Caucasian hinterland to revolutionary Moscow: the underground, arrests, barricades. Khlebnikov, leaving the south, wandered around Russia, studied in Kazan and St. Petersburg, and searched for a new language of the time. Bialik, after the forests of Volhynia, found himself in a yeshiva and then in Odessa, where he became the voice of Jewish poetry. Their paths lay through different geographies— the Caucasus, Volhynia, the steppes, the capital’s squares—but they were all united by a sense of a turning point in history.

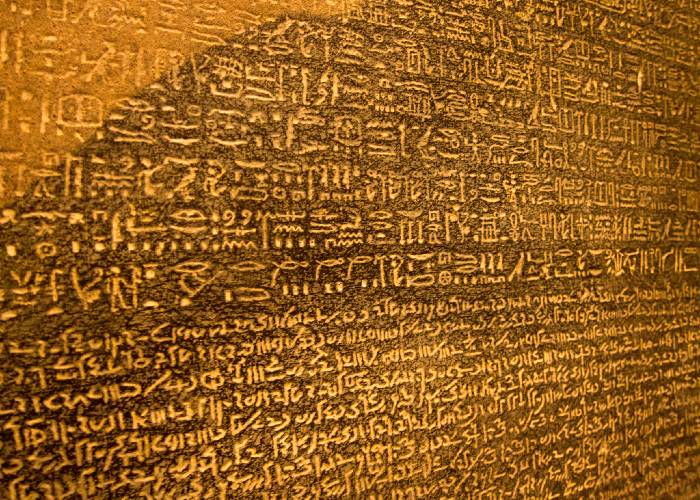

Mayakovsky and Khlebnikov met in futurism, in their rejection of the old language. The first was a propagandist of the revolution, the second an experimenter with forms and words. Bialik did not know them personally, but the sound of his Hebrew led in the same direction—the renewal of language, the connection between the past and the future. All three perceived poetry as action.

The ends of their lives were tragic. Mayakovsky shot himself in 1930; his brain, removed for research, became a symbol of science’s attempt to comprehend genius. Khlebnikov died in 1922, forgotten and unhappy. Bialik died in 1934 in Vienna and was buried in Tel Aviv as a national poet. Their deaths did not destroy what they had created—their words remained alive.

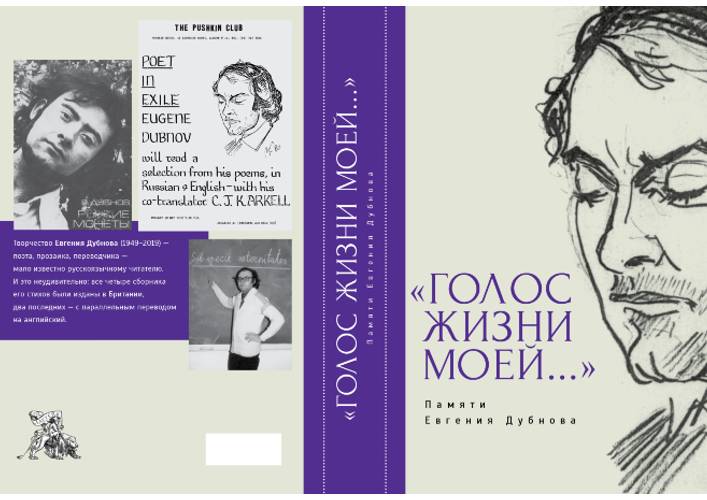

Berberova called this generation a broken chain. Some died, others faded away in exile, but they were all connected by the bloodstream of the era.