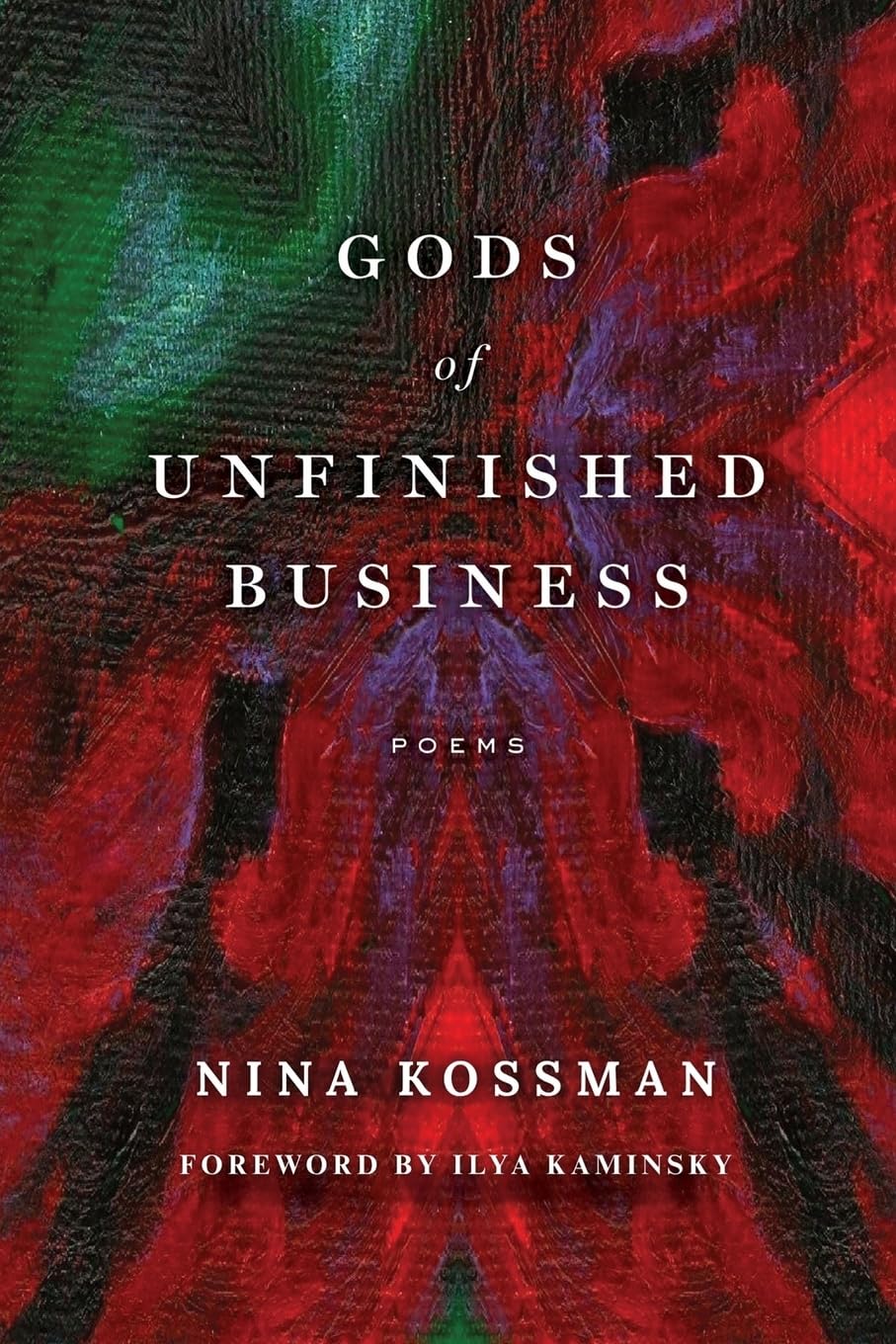

1

Катя так скучает по Мише, что у неё всё болит от макушки до самых пят. Она его-себя-обнимает, когда все в секции мирно спят. Катя гладит себя по бокам и попе, на попе теперь целлюлит. Так бывает, если никто не гладит, думает Катя, сворачивается и скулит. Катя пробует быть потише, но в горле сильно першит. Она вспоминает, как Миша держал её за руку, если следователь разрешит. Как он говорил: не волнуйся, маленький, тюрьма — это всё же не смерть, не рак… Катя потом засыпает и видит дерево, которое смотрит с промки на их барак.

Дерево так скучает по Кате, что у него все болит, от кроны до самых корней. Дерево тянет к бараку ветки, и ветки становятся все длинней. Дерево вырастило цветок, один, чтобы ей показать, одной. Но Катя опять не пришла, потому что работы мало и бригаде дали внеплановый выходной. Такой вышел цветок красивый, рыдает дерево, прозрачный и розовый на просвет. Дерево смотрит в окно столовой, глазами другого дерева, но Кати и там почему-то нет. Оно тянется к медсанчасти, передавая сигналы растущим вблизи кустам. Может, у Кати сердечный приступ, тогда она точно там? А может Катя уже в больнице, и после её актируют навсегда? Дерево-мастер себя накручивать. Это да.

Катя обычно приходит к дереву, как только бригада пройдет развод. Утыкается в его шершавый сухой живот. Думает, гладя рукой кору: я больше не выдержу. Я нафиг совсем умру. Вот завтра вообще не встану, возьму и буду лежать в кровати. А лучше бы стать бы птицей! — такие мысли банальные в голову лезут Кате, — Каким-нибудь сраным голубем, живущим на сраной крыше. Чуть-чуть поживу и свалю оттуда, под Тулу, к Мише, в мужскую его колонию. Там, конечно, режим построже, но он на меня посмотрит и голубем станет тоже…

Не стать тебе, дура, голубем! Чё придумала, вот потеха! — думает голубь, сидящий на крыше второго цеха. Он провожает Катю косым и недобрым взглядом. Голубь так любит дерево, что даже боится садиться рядом, чтобы, когда он решится насрать на Катю, случайно любимое не задеть снарядом. Голубь молча любуется каждой веткой и смотрит на поле, лежащее за запреткой.

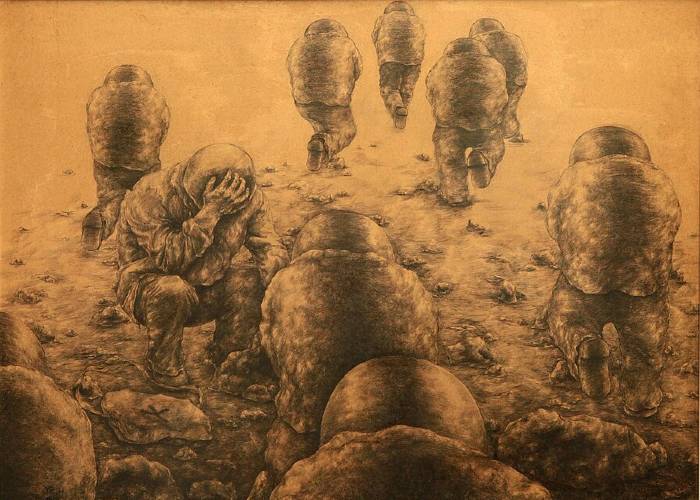

А в поле кашка и душица, там нет ни мерсов, ни тойот. А Катя на шконарь ложится, лежит и больше не встает. Лежит на завтрак, на проверку, как мёртвый кит, как дохлый лось, лежит, подобно фейерверку, в реке промокшему насквозь, лежит, прибитая неволей, лежит, и вид её суров, лежит, не слыша грозных воплей разнообразных оперов, лежит, как ржавая граната, как член, что в холоде поник, как на пороге деканата лежит нетрезвый выпускник. Она не злится, не рыдает, не строит замков из песка. Одна тоска её съедает, тупая, вязкая тоска, как чьи-то волосы из слива, как лук, разваренный в борще… И так же дереву тоскливо.

А голубю — окей вообще. Наверно, с наших колоколен он безъязыкий идиёт, но голубь полностью доволен, что Катя больше не встаёт. Никто теперь не суетится, не плачет, не наводит жуть. Он птица. Он на то и птица, чтоб думать быстро и чуть-чуть. Да пусть она вообще хоть сдохнет! Чума, чума на этот дом! Но дерево стоит и сохнет, и это голубю серпом по яйцам. Кстати, голубь-самка, домохозяйка от и до, ему вообще не нужно замка, а нужно прочное гнездо. Ему бы всякого земного, поближе к веткам и коре… Но дерево! Ему хреново! Оно, любимое, в депре…

И голубь, свидетель чужой безответной страсти, утром летит к бараку и к медсанчасти. Смотрит, как бродят Оли, Марины, Насти, толпы с зелёным низом и белым верхом, равно подобные вымокшим фейерверкам, все на одно лицо, по голубиным меркам. И среди них какие-то в серых пятнах, в диапазоне от странных до неприятных, возле барака плотным кольцом стоят, нахмурившись. Тихо слышится: «вот некстати!». Голубь крадется с видом полночной тати и, среди серых, вдруг ловит взгляд проклятущей Кати. Катя лежит на земле. На выцветшем одеяле. Краска с её лица как будто сползла слоями. Зубы блестят, как у волка в загонной яме. Голубь орёт, выразительно, но негромко. Двадцать секунд полёта, и снова промка.

Сто сотен оттенков серого, скучнейшая из картин, и в центре картины дерево пустило цветок, один. Оно всю дорогу верило, что Катя придёт сама, Оно ведь на то и дерево, чтобы молча сходить с ума. Когда уже всё посчитано, и в цехе провыл звонок, так милую ждать мучительно в отсутсвии рук и ног. Стоит оно, словно голое, как будто по веткам ток… И вдруг замечает голубя. Который! Дерёт! Цветок!

Стой, стой! — закричало бы дерево, — это для Кати, я должен его беречь! Стой, стой! — закричало бы дерево, но в этом рассказе автор запрещает себе прямую речь. Поэтому дерево просто стоит и смотрит, как какой-то сраный голубь подлетает, отгрызает ветку, что-то кричит и улетает. Наверняка потащил мою веточку в свое сраное гнездо, своим сраным птенцам, — тоскливо думает дерево. — Видело я голубиных детей, самые уродливые существа в мире. Им же всё равно, на чём сидеть, и мамаше их — тем более! Дерево шуршит листьями. Это оно так плачет.

2

А голубь летит обратно к бараку, туда, где Катю уже готовятся поднять на одеяле и нести к воротам, чтоб там погрузить в скорую. Катя пустыми глазами смотрит в пустое небо, когда в нем появляется голубь с веткой в клюве.

Офигеть, думает Катя. Голубь с ветвью в клюве! Или это я уже померла, или потоп скоро закончится, и все твари со своими парами выйдут на волю вольную, на сушу сухую, на жизнь живую. Ну тогда ладно, придется пока не помирать, раз Миша — а кто же еще это мог быть — отправил мне такую милую птичку с таким красивым цветком… Катя садится на одеяле и что-то говорит пятнистым людям. Люди кричат, машут руками, а Катя смеется и прижимает к груди ветку.

Но голубь всего этого уже не видит и не слышит. Он летит в поле и там орет, а потом вываливает на головы кашек и ромашек целую кучу негатива. Потому что к дереву он должен вернуться легким и чистым, потому что дерево ни в чем не виновато, потому что завтра придет Катя и обнимет дерево, и они там будут шептаться и вокруг должно быть сухо. Ну, или не завтра, а через недельку, когда выйдет из ШИЗО, — мстительно думает голубь. Он, конечно, птица мира и все такое, но тоже, в конце концов, живой человек!

…Так много любви, размышляет навозный жук, вонючий шарик по полю перед собой толкая. Так много любви в этом проклятом месте, и вся какая-то не такая. Конечно, хотелось бы больше радости, чтобы всякий там мир, покой… Но пусть хоть такая будет.

Все-таки лучше, чем никакой.

(22.08.2025, ИК «Прибрежный»)

* * *

1

Katya misses Misha so much that everything hurts, from her head to her toes. When everyone’s deep asleep in her unit, she pretends that she’s holding him close. Katya strokes her own sides and her bum; the bum now has cellulite. That’s what happens if you don’t get any loving, thinks Katya, and cries in the night. Katya tries to be quiet, but her throat is all scratchy and doesn’t feel good. She remembers how Misha held her hand when the investigator said he could. How he told her, don’t worry, babe, it’s just jail after all, not cancer or death… Katya sleeps and dreams of a tree in the work zone across the path. The tree misses Katya so much that everything hurts, from its crown to its roots. The tree stretches toward the barracks and grows longer shoots. The tree grows a flower, just one perfect bloom, for her sake. But Katya still hasn’t come: there was too little work and her work brigade got a break.

The blossom has turned out so pretty, the tree wails, its petals are rosy and sheer. The tree peers into the mess hall, via another tree, but Katya’s not there. The tree stretches toward the infirmary, sending signals to shrubs at its side. Maybe she’s had a heart attack and is being treated inside? Or maybe she’s at the hospital, and it’s all over for her? The tree is a master at spiralling—that is for sure.

Katya usually comes to the tree just before her brigade begins work. She nestles against its rough belly and strokes its dry bark. She thinks to herself as she stands there alone. I’m going to die. I can’t take this, I’m done. I won’t get up tomorrow. I just won’t. I’ll stay in my bed. If I could only turn into a bird!—these silly thoughts are churning in Katya’s head. If I could turn into any shitty old pigeon, out on some old shitty roof. I’d leave it and head toward Tula, where Misha is held, I’d just fly off. At the men’s colony it’s really tough, so he’d give me one look and also turn into a dove…

Neither of you can turn into doves, you moron! You don’t have a hope!—thinks the pigeon looking down at Katya from the roof of the second workshop. The pigeon doesn’t like Katya. It gives her an evil glare. But it loves the tree so much that it fears getting too near, so that when it finally shits down on Katya, the beloved tree isn’t left with a smear. The pigeon treasures the tree and its branches—every last one, as it looks out at the field beyond the no-go zone.

Out in the field there is clover, but there’s no cars, trucks, or pickups. And Katya says that it’s over—she lies down and doesn’t get up. She’s flat out for breakfast and roll call, like a downed moose, like a beached whale, like a set of fireworks that fell into a river and are now a fail, she lies there, done in by bondage, she lies there looking stern and hard, not listening to angry shouting of all the officers and guards. She’s down like a grenade that rusted, or like a penis gone limp in the cold, or like a graduate who’s busted drunk and unconscious on the dean’s threshold. She is not angry, she’s not weeping, not building castles in the air. She is consumed by awful sadness, by dull and desperate despair. She’s done, like hair that clogs the shower, or like an onion boiled all day… The tree is likewise feeling sour.

But the pigeon is doing okay. Of course, from our perspective, the pigeon is a nonverbal chump, but it is feeling pretty festive now that Katya no longer gets up. Now there’s no one getting frantic, no one is weeping till you want to spit. The pigeon is a bird, so it is fitting that it thinks quickly and only for a bit. For all it cares, Katya can go and croak! A plague, upon her house, a plague! But now the precious tree just sulks there, and that the pigeon cannot take! By the way, the pigeon is female, a homemaker if there ever was one, it has no need for a castle, just a sturdy nest to call home. It is down-to-earth as it can be, it wants closeness to the branches and bark… But the tree is depressed now, you see! Yes, the beloved tree is feeling dark…

And so, the pigeon, witness to unrequited passion, flies in the morning to the infirmary section. It watches crowds of Olgas and Marinas in action, trudging around in green bottoms, white tops, like those wet fireworks that were fated to flop—to a pigeon all looking like peas in a pod. Among them are some others, mottled with grey, ranging from unpleasant to merely strange, who stand now by the barracks, looking outraged. They hiss to each other, “It’s bad timing, alright!” The pigeon steals closer, like a thief in the night. And it sees that damned Katya, looking a fright. Katya’s lying flat on the ground. On a faded old wraparound. Her face looks ghastly, all colour is gone, her teeth are bared, like a wolf hunted down. The pigeon screams, quietly, but with expression. It takes off and flies back to the work zone section.

In the work zone it’s just shades of gray—boredom and gloom, but there stands the tree, with its single bright bloom. All this time the tree had faith that Katya would soon return. It’s a tree after all, made to madly and silently yearn. When everything has been tallied, and the end-of-work signal howls, it’s torture to wait for the one you love, when you’re lacking both legs and arms. The tree stands there as if buck naked, as if current runs through its crown… A that’s when it sees the pigeon. That pigeon! Pulls! The bloom! Down!

Stop, stop!—the tree would have shouted—that’s for Katya, I must save it for her! Stop, stop!—the tree would have shouted, but in this story the author decided to avoid direct speech. This is why the tree just stands there and watches some shitty pigeon fly over, gnaw off one of its branches, screech something, and fly off. It’s taking my branch for its shitty nest, for its shitty babies—thinks the tree sadly. I know what baby pigeons look like: they’re the ugliest creatures alive. They don’t give a care what they’re sitting on, and their mama cares even less than they do. The tree rustles its leaves. That’s how trees cry.

2

And the pigeon flies back to the barracks, where Katya is about to be lifted up and carried toward the gates, to be loaded into the ambulance. Katya is staring vacantly into the vacant skies when, all of a sudden, a pigeon appears, holding a branch in its beak.

Holy crap, thinks Katya. A pigeon with a branch in its beak! Either I’ve died already, or the flood is about to end, and all the animals in their pairs will come out of the ark to freedom, to dry soil, to live their lives. Well, okay then, I’ll have to keep living for now, if Misha—because who else could it be—sent me such a lovely bird with such a beautiful flower… Katya sits up and says something to the motley grey people surrounding her. The people shout and wave their hands around, and Katya laughs and hugs the branch to her chest.

But the pigeon doesn’t see or hear any of this. It flies out to the field and screams there, and then dumps a whole slew of negativity on the clover and the daisies. Because it must return to the tree full of sweetness and light, because none of this is the tree’s fault, because tomorrow Katya will come and embrace the tree, and they’ll whisper sweet nothings to each other, and everything around them must be dry. Well, if not tomorrow, then in a week’s time, when she gets out of solitary—the pigeon thinks spitefully. It’s the bird of peace, and all that, but it still has feelings!

…There’s so much love, muses the dung beetle, its reeking ball by its side. There’s so much love in this damned place, and somehow none of it’s right. Yes, it would be nice to have more calm, joy, and fun… But let’s have at least this. This kind is better than none.

(22.08.2025 “Pribrezhnyi” Penal Colony)