* * *

The best time is the darkness

of morning after a night shift.

Streaks on the kitchen window,

compact comfort awaits like a pet.

This is the world on pause,

halting its pistons and chains.

This apartment is the best place.

Have a cup of strong tea.

No one else can help me

vanquish my own life.

The best sight I’ve seen

is my daughter, asleep.

The best thing I’ve heard

is you, talking through your sleep:

“Honey, you smell like smoke…”–

then blessed silence begins.

Лучшее время — в потемках

утра, после ночной

смены, окно в потеках,

краткий уют ручной.

Вот остановка мира,

поршней его, цепей.

Лучшее место — квартира.

Крепкого чая попей.

Мне никто не поможет

жизнь свою превозмочь.

Лучшее, что я видел —

это спящая дочь.

Лучшее, что я слышал —

как сквозь сон говоришь:

«Ты кочегаркой пахнешь…» —

и наступает тишь.

* * *

I’m going home, I’m done, I’m done,

my shift was finally over–

the bus was crossing Kresty Bridge–

and I thought: God, life is so simple,

how everything assumes its forms–

trees, pipes, and sleet

careening past, and boathouses

tucked into snow, asleep,

and everything keeps quiet, cropped

by the window’s slanted square,

rushing towards me, flitting past,

swept by the setting sun,

and out there, on gray surfaces,

people submit, people subdue,

bury their loved ones, love, and wait

for guests to come, and live and die,

and it’s time to open the door,

and it’s time to brew some strong tea.

Домой, домой, домой,

с Крестовского съезжая

моста, я вздрогнул: боже мой,

какая жизнь простая,

как всё проявлено: торчат

деревья, трубы,

и мокрый снег летит, и спят

в снегу гребные клубы,

и всё молчит, срезаясь за

стекло косым квадратом,

то набегая, то сквозя,

то волочась закатом,

а там, средь серых плоскостей,

смиряются, смиряют,

хоронят, любят, ждут гостей,

живут и умирают,

и надо двери отворить,

и надо чаю заварить.

* * *

From winter, I will take the luminous square

of the window, a phosphorescent shard glowing

in a room where a Christmas tree slumbers

(we’d saved up, spent our last pennies on it).

From a fading lamp, I will take our poor everyday grind

(a green needle, stuck between the floorboards).

Our love lasts, of course, but duty lasts longer;

we do what we must, so help us Grief.

Closer, closer: I will bring to my eyes

the Christmas tree stand, its criss-cross

shadow falling on the building next door. This

yellow light–may it not be forgotten.

And your face like an oval, I’ll see it close,

the curve of your arm, a bit of laziness

as you put your book away–reading?

forget it, we rise so early–fadeout, fadeout.

I’ll take it all: whether drunken men shouting

in the courtyard, or boots creaking, sprinting

off to work, or echoes in the grotto-like entrance

to our apartment building, icy boulder shine,

or a kitchen sunrise–I guess brewed it last night

nice and strong… so, time to go to work…

We’ll sleep in on Saturday, darling, won’t we.

Saturday does not come for a long, long time.

And when the polar night covers us with warm wool

(could be my papa’s jacket); and when that snow

reaches for streetlamps, and crafts its lace

circle patterns, and our daughter awakes,

scared for us–do you remember being a small child,

that fiery labor?–then the holidays will arrive,

looking over her starched bed,

stringing golden garlands, and everything will be saved.

Я возьму светящийся той зимы квадрат

(вроде фосфорного осколка

в черной комнате, где ночует елка),

непомерных для нашей зарплаты трат,

я возьму в слабеющей лампе бедный быт

(меж паркетинами иголка),

дольше нашего — только чувство долга,

Богом, радуйся горю, ты не забыт.

Близко, близко поднесу я к глазам окно

с крестовиной, упавшей тенью

на соседний дом, никогда забвенью

поглотить этот желтый свет не дано.

И лица твоего я увижу овал,

руку с легкой в изгибе ленью,

отстранившую книгу, — куда там чтенью,

подниматься так рано, провал, провал.

Крики пьяных двора или кирзовый скрип,

торопящийся в свою роту,

подберу в подворотне, подобной гроту,

ледяное возьму я мерцанье глыб,

со вчера заваренный я возьму рассвет

в кухне… стало быть, на работу…

отоспимся, радость моя, в субботу,

долго нет ее, долго субботы нет.

А когда полярная нас укроет ночь

офицерской вполне шинелью,

и когда потянется к рукоделью

снег в кругах фонарей, и проснется дочь,

испугавшись за нас, — помнишь пламенный труд

быть младенцем? — то, канителью

над ее крахмальной склонясь постелью,

вдруг наступят праздники и все спасут.

* * *

September Day

My fifty-second year found me

at the home of a friend. Appeal denied,

it said. As I sat by the table, a tree

outside reached out an almost-hand,

bandaged in torn leaves,

green, red, and yellow.

Marked with shards of clear glass

from a celestial window.

The sky, clearing after a thunderstorm.

Like a child whose guilty mind

hasn’t hobbled him. Who doesn’t know

posturing yet. He is the harbinger of the light.

But you beggar tree, why the hand?

Are you growing up? What do you need from me?

Some soul? Here, eat.

I’ve got too much. Get silly off me.

Then the light faded, the judgment

went into effect, no further appeal.

And I mumbled, This is it–this is it–

darkness–and went back to the birthday table.

27 сентября 2000

День в сентябре

Пятьдесят вторая меня застала

осень (чем не статья?) в доме друга.

Из-за окна, пока я сидел у стола,

дерева тянулась, тянулась почти рука,

перевязанная рваным бинтом

листвы зелено-красно-желтым

и осыпанная прозрачным, битым

с неба высаженного стеклом.

Проясненное небо после грозы. —

Так ребенок, в котором совесть

не завесила еще взгляд, не знает позы.

Он световая весть.

Но зачем же нищее тянешь

руку дерево? Ты взрослеешь? Чем

ты разжиться хочешь? Душой? На, ешь.

На, глупей, мне столько незачем.

И тогда опять потемнело, словно

приговор обжалованью, вступая в силу,

не подлежал и, приговаривая: темно,

все, темно, темно, — подошел к столу.

27 сентября 2000

Translated from Russian by Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco

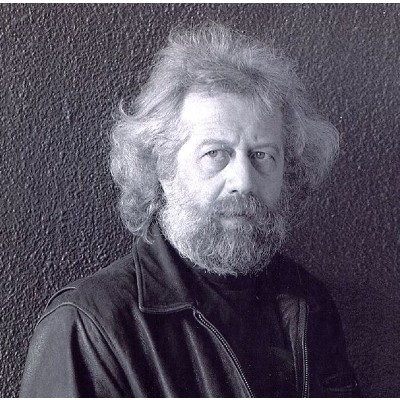

Vladimir Gandelsman is the 2011 recipient of the highest award for poetry, the Moscow Reckoning Prize. He was born in 1948 in Leningrad, and has been living in the United States since 1990. Gandelsman is the author of eighteen poetry collections and two volumes of collected works, as well as numerous translations of British and American poets into Russian.

Launched in 2012, “Four Centuries” is an international electronic magazine of Russian poetry in translation.

“The Lingering Twilight” (“Сумерки”) is Marina Eskin’s fifth book of poems. In Russian.

A collection of moving, often funny vignettes about a childhood spent in the Soviet Union.

“Vivid picture of life behind the Iron Curtain.” —Booklist

“This unique book will serve to promote discussions of freedom.” —School Library Journal

A new collection of poems by Ian Probstein. (In Russian)

Young readers will love this delightful work of children’s verse by poet William Conelly, accompanied by Nadia Kossman’s imaginative, evocative illustrations.

A book of poems by Maria Galina, put together and completed exactly one day before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This is Galina’s seventh book of poems. With translations by Anna Halberstadt and Ainsley Morse.