ПИСЬМА, ОСТАВЛЕННЫЕ НА ОЭЛЕ

I

Камбрия-Хайтс. Монтефиоре, Мекка евреев.

Полнолуние, кладбищенское время.

Добро пожаловать в загробный офис реб Шнеерсона.

Я думала, здесь будут только одетые по одному фасону

хасиды в нелепом своем наряде,

но вижу женщин в обычных платьях,

девчонок, непримечательных с виду.

Был такой детский шампунь “Без слез”

задуманный, видно, хасидом.

Постараюсь без слез.

Ухо улавливает вавилонский разброс

(но шепотом, шепотом, если можно).

Комната напоминает зал ожидания перед дверью таможенника,

раздевалку в школе или спортивном зале:

пластиковая поверхность, сменная обувь, вешалка для шалей.

Разнокалиберный люд пишет список желаний.

II

Я заглядываю в себя и в псалмы.

Я ищу подобающие слова, но молитвенник говорит совсем о другом.

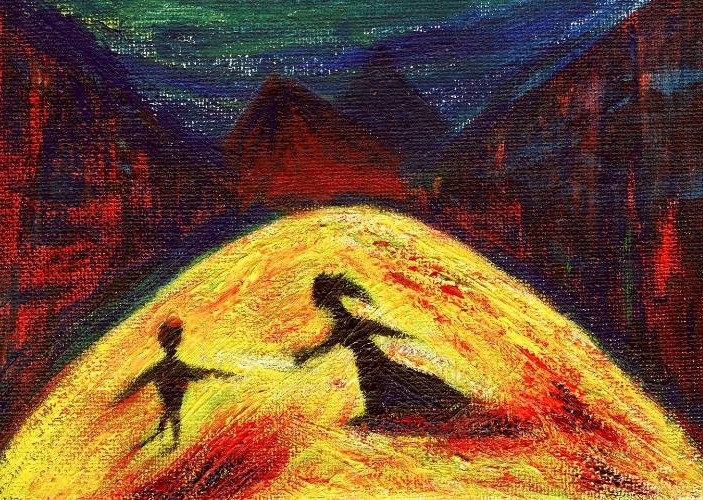

Зато внизу, в бетонной квадратной ванне,

в купальне просьб и слез,

среди разорванных белых записок

(иногда выныривают суетные цветные —

накладные, настенные календари,

билеты в кино, чьи-то фото),

чернильные строчки — как стрелы устремлены

в небо; строчки протягивают руки,

как запоздалые ночные пловцы.

Сделaй так, чтобы… had to ask Thee…

…хорошо?…

Please Hashem… Hash…

На всех доступных языках

захлебываются в разноголосицe,

выкликают

имя Б-га, шипящее, как пенный напиток,

имя Б-га,

бутылочный осколок в песке,

просящий тишины.

Нам ли не знать, как Oн нетерпелив

и не всегда логичен.

Но, пока я колеблюсь, просить ли,

из молитвенника выпадает

кем-то оставленная записка “Выше нос, все уладится” —

и я понимаю, что выслушана сегодня.

_____________

О’эль – место упокоения Седьмого любавического Ребе, Менахема-Мендела

Шнеерсона.

МОИ ПОГРОМЫ

Помню, бабушка рассказывала, что их никогда не трогали:

Папа-мясник приберегал филе для околоточного,

а на праздник давал гуся.

Я представляла себе погром, как сцену из фильма «Свадьба»,

с перьями, летящими по ветру.

В восьмидесятые бабушка вздумала перебивать подушки.

Перья гусей, усопших до революции

взяток околоточному, осторожно пересыпались в новые наперники,

а я боялась, что мы ненароком вызовем дух погрома.

И что же, допересыпались!

В апреле восемьдесят девятого зашептали.

Ждите, в день рождения Гитлера.

Уезжали бы в свой Израиль.

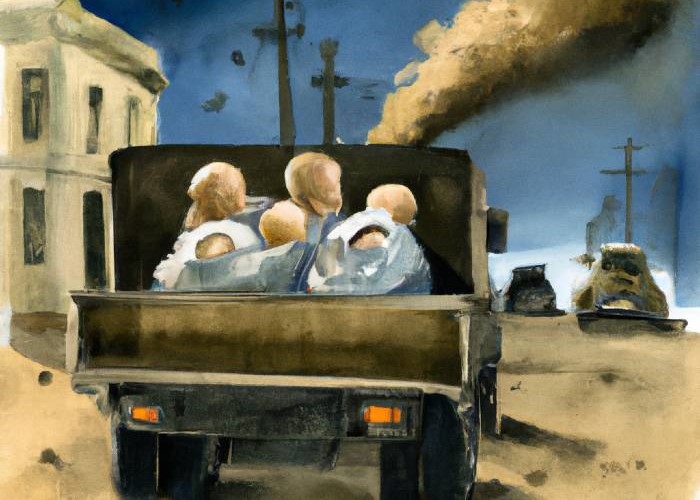

Некоторые уехали.

Девятнадцатого апреля замолчал телефон.

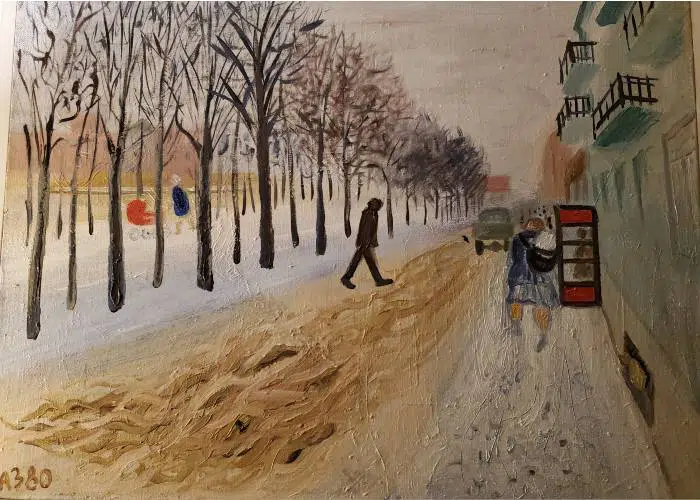

Город прятал глаза. Я шла с малышом на прогулку,

избегая встречаться взглядами:

зачем ставить людей в неловкое положение?

Мне, кстати, с детства было стыдно до слез

за антисемитов, было жалко — их,

невиноватых, взращенных в упряжке с ненавистью.

Во время дневного сна позвонили двое: безбашенный Вова,

сказавший, что если решимся проехаться ближе к ночи,

то у него есть кастет для погромщиков и подушки для нас,

и Алена, рационально рассудившая, что бабушка

сдаст с удовольствием взрослых жидов, но никогда не выдаст ребенка.

Мы решили остаться дома.

Все обошлось без перьев.

Вскоре решили уехать совсем.

Но навсегда запомнили, как пахнет ожидание погрома.

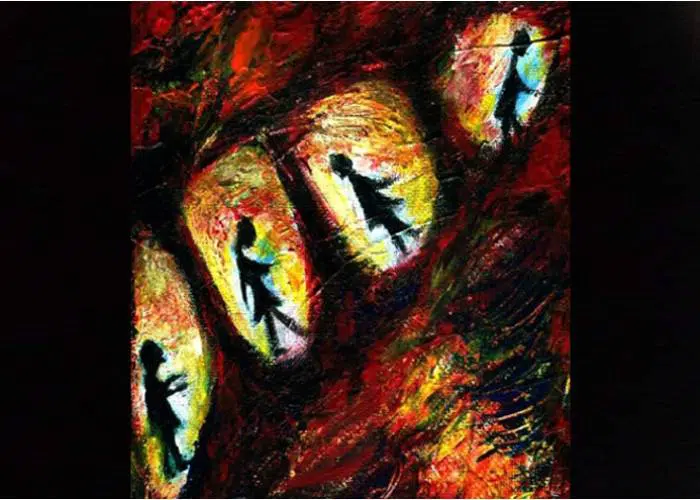

Иногда самый воздух наполнен погромом,

как однажды в предпасхальной Москве,

как однажды в амманском автобусе,

как в опасной толпе подростков,

раззадоривающей себя.

Сегодня другой мой город, ставший давно родным,

опустел и молчит, ожидая сигнал к погрому.

То ли я потеряла чутье, то ли совсем не боюсь их,

но никто не отводит глаза.

Вот она я, на улице…

Нью-Йорк, 10/13/2023

Letters Left at the Ohel

I.

Cambria Heights. The Jewish Mecca—Montefiore.

The month is at full-moon, a time for cemeteries.

Welcome to the after-life office of Reb Schneerson.

I thought I would find here Hasidim alone,

dressed in their garb, absurd and uniformal,

but I see women, wearing something normal,

and girls, unexceptional from every facet,

There was a kids’ shampoo, called “Tear-Free,”

that must’ve been dreamed up by a Hasid.

I’ll try to keep this tear-free.

My ears detect a babel of tongues

(but kindly keep it to a whisper, please).

This looks like a room at border services,

or a change room at a gym or a school:

plastic surfaces, slippers, hangers for shawls.

Sundry folk write their requests, one and all.

II.

I peer into myself and the psalms.

I search for the right words, but the prayer book talks

about something else entirely.

Yet below, in a square cement basin,

that bath of entreaties and tears,

among the torn white notes

(occasionally, coloured worldly ones—

invoices, wall calendars,

movie tickets, random photos)

ink-written lines aim like arrows

into the sky; the lines reach out

like late night swimmers

Make it so that… had to ask You…

…alright?…

Please Hashem… Hash…

All the available languages,

sputtering in a dissonant chorus

calling out

the name of God that fizzes like soda,

the name of God

that’s like a bottle shard in the sand

requesting stillness.

We know all too well how exasperated

He can be and illogical.

But as I’m wavering, to ask or not to ask,

someone’s note slips out of the prayer book:

“Hang in there, it’ll all work out” –

and I understand that today I’ve been heard.

My Pogroms

Grandma used to say that no one ever laid a hand on them:

her father the butcher would put aside a nice filet for the local police chief,

and get him a goose for the holidays.

I used to imagine a pogrom as a scene from the classic film The Wedding,

feathers flying through the air.

Back in the eighties, grandma decided to make new pillows out of her old ones.

Feathers of geese slaughtered before the revolution,

bribes for the police chief, were carefully transferred into new pillow liners,

as I worried that we might accidentally summon the pogrom spirit.

And, what do you know, we had!

In April of ’89 the whispers began.

Just you wait, Hitler’s birthday is coming.

Why don’t you go to that Israel of yours.

Some did.

On the 19th of April our phone went silent.

Our town averted its eyes.

I took my toddler for a walk,

avoiding meeting eyes with people we knew:

why make people uncomfortable?

I felt embarrassed for the antisemites ever since I was a child.

I felt sorry for them—all those who demeaned themselves

by their baseless hatred.

During the afternoon nap, I got two phone calls: one from reckless Vova,

who said that if we’d like to stay with him, he’s got brass knuckles for the pogromshchiki and some pillows for us,

and the other one from Alyona, who rationally concluded that while her grandma

might be overjoyed to hand over the adult Yids, she’d never do that to a child.

We decided to stay home.

In the end, there were no feathers.

Soon after we decided to leave.

But we learned once and for all how it feels: that expectation of a pogrom.

Sometimes, the air itself is heavy with pogrom,

as it was once in Moscow before Passover,

as it was once on a bus in Amman,

in a dangerous crowd of youngsters

who were winding themselves up.

Today another town, which has long become my own,

is empty and silent, expecting a pogrom.

Maybe I lost my feel for it, maybe I’m just no longer afraid,

but no one is averting their eyes.

Here I am, out on a Brooklyn street…